Maps of the Pacific

Maps of the Pacific

Explore the beauty, art and science of mapping across three centuries through an exhibition of maps, charts, atlases and globes featuring the Pacific, held in the Library's magnificent collection.

Location

Maps of the Pacific

Explore the beauty, art and science of mapping across three centuries through an exhibition of maps, charts, atlases and globes featuring the Pacific, held in the Library's magnificent collection.

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest ocean on earth, extending from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean in the south, bounded by the continents of Asia and Australia in the west and the Americas in the east. This vast ocean was named the Pacific by the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan in 1520, despite having been explored and inhabited thousands of years earlier.

Another three centuries passed before this expanse would be accurately mapped and understood by Europeans, identifying over 20,000 islands and communities across more than 155 million square kilometres. This exhibition traces the European mapping of the Pacific across the centuries — an endeavour that elevated the science and art of European mapmaking. Redrawing the map of the world ultimately facilitated an era of brutal colonisation and dispossession for many Pacific First Nations communities.

Maps of the Pacific is presented with support from the State Library of NSW Foundation.

Exhibition highlights

There is plenty to consider in this world map by Sebastian Münster including the gruesome scene of cannibals in the lower left corner. The elaborate borders are attributed to the well-known German artist Hans Holbein the Younger.

In 1589 Ortelius produced Maris Pacifici, the first dedicated Pacific map. It is probable that Ortelius used Frans Hogenberg’s 1589 map of America as its basis but expanded further west. The magnificent illustration of a ship being guided across the Pacific by an angel depicts the Victoria, the only one of Magellan’s five vessels to complete the first circumnavigation of the world.

This chart of the southern tip of South America includes many of the extravagant decorative features perfected by mapmakers in the 17th century. The ornate strapwork of the cartouche is supported by two penguins, and profiles of the cliffs encountered along the strait sit within a separate cartouche. Note that the compass rose points downward, indicating north is at the bottom of the chart.

Tierra del Fuego lies within the imagined southern continent as Cape Horn had still not been explored and charted. It was only in 1616 that Le Maire and Schouten rounded the tip of South America.

This world map was prepared by Joan Blaeu for his Atlas Maior in 1662. Classical gods, representing the planets orbiting the heavens, decorate the map’s upper margins. An astronomer, holding an armillary sphere (a planetary model), and a geographer, taking measurements of the globe, flank the hemispheres. Allegories of the seasons decorate the lower margin.

Acclaimed as the largest and most splendid atlas of the 17th century, the Atlas Maior was published in 12 volumes by Joan Blaeu between 1662–65. The frontispiece (decorated title page) of the atlas displays the crowned figure of Cybele, the Greco-Roman earth goddess, in a chariot led by lions. She is surrounded by four female figures and their companion animals, representing the known continents.

This 18th century Pacific map is one of the most ornate examples of the period, featuring dozens of illustrated scenes that show cultural practices, customs, histories, flora and fauna of North and South America. These vignettes, including one depicting a human sacrifice, reduce other cultures to ‘curiosities.’ They also suggest that the Pacific might hold many natural resources that could be exploited. The inclusion of explorer tracks across the ocean indicate how the Pacific would be incorporated into European trading networks.

Tupaia was a talented navigator, scholar and artist from Raiatea in French Polynesia. He chose to join Cook’s voyage in 1769. His knowledge of Polynesian customs and language was invaluable, and his navigation skills were essential as he piloted the Endeavour through the scattered islands south of Tahiti. Despite his incredible knowledge and skill, Tupaia was often the subject of racism and derision by members of the crew. Tupaia remained with the expedition until they reached Batavia, where he died from dysentery or malaria in 1770.

At some stage during the voyage Tupaia produced a sketch describing the 74 islands radiating out from Tahiti. His original sketch is lost but Cook’s copy survives in the papers of Sir Joseph Banks at the British Library. A printed version, a European interpretation of Tupaia’s chart, was published by Johann Forster who sailed on Cook’s second voyage.

Tupaia’s chart did not fix the location of the islands according to the traditions of a European chart. Most likely sharing Polynesian navigation techniques, he was explaining the relationships between islands, and sailing directions from Tahiti as the central point.

Because they weren’t looking at it through his eyes ... the code of that map still lies with Tupaia. The drawings were his way of crossing the language barrier.

Jack Thatcher, Maori Master Celestial Navigator, 2021

This is the first decorative map recording the Endeavour’s voyage of exploration to Australia, New Zealand, and the South Pacific, as well as showing the tracks of Carteret, Byron and Wallis. The ship depicted in the vignette is almost certainly Cook’s ship, the Endeavour.

Antonio Zatta was an Italian mapmaker and publisher whose decorative maps provided a contrast to the more austere and technical maps from the same period.

The Arrowsmith family was one of London’s leading publishers of maps and charts in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. This chart, published in nine sheets, was Aaron Arrowsmith’s most important contribution to the mapping of the Pacific. It was published in several editions from 1798 through to 1832.

This chart includes all European knowledge of the Pacific up to the date of publication in 1798, including James Cook’s three voyages. It was dedicated to Joseph Mendoza y Rios, a Spanish astronomer and mathematician, known for his work on navigation and production of astronomical tables for navigation.

Before Europeans practised astronomy and explored the stars, the First Nations inhabitants of the Pacific region understood the significance of the Southern Cross within the night sky. Their knowledge of the movement of the moon and stars guided travel across the ocean, predicted the weather, and initiated important cultural ceremonies

The five stars of the Southern Cross are the brightest features in the constellation named Crux, Latin for cross. The two brightest stars, Acrux and Gacrux, point the way to the Southern Celestial Pole.

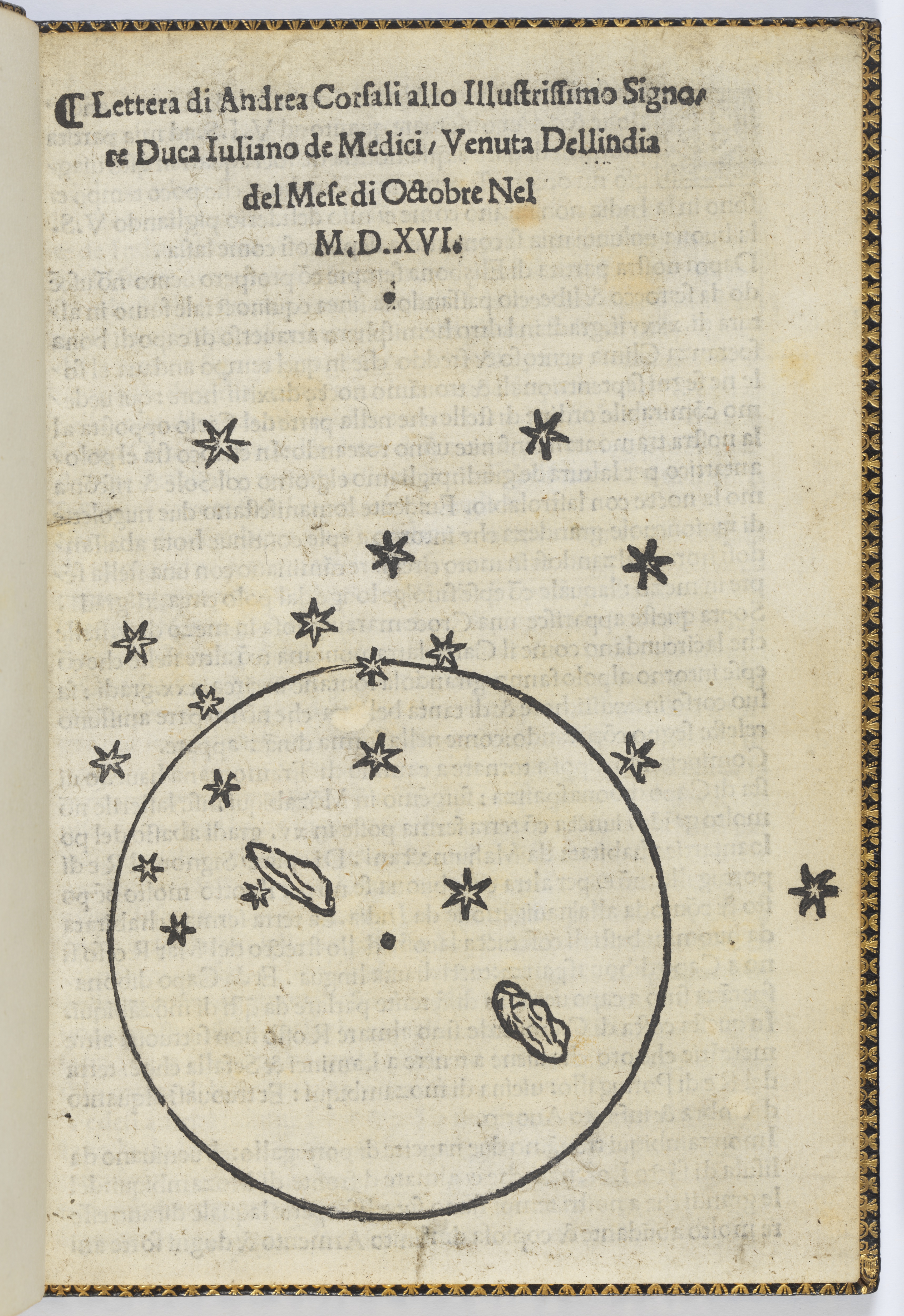

In 1504 Italian navigator Amerigo Vespucci wrote the first description of the constellation in a report to his patron, Lorenzo de Medici. In 1515 Italian navigator Andrea Corsali observed the Southern Cross while on a Portuguese expedition to India and sent his observations to his patron, Giuliano de Medici, in Florence:

This cross is so fair and beautiful that none other heavenly sign may be compared to it …

Corsali’s letter was privately published soon after it was received, making it one of the earliest illustrations of the Southern Cross in print. There are only four known copies of this publication, printed for private circulation within the Medici family.

Vincenzo Coronelli was an Italian friar, cosmographer, cartographer, and publisher, famous for his creation of two magnificent globes for Louis XIV completed in 1688. In 1693 he published these gores (curved sections intended to be applied onto a sphere) for a smaller celestial globe. They were printed in Paris by Jean Baptiste Nolin, the engraver to the King of France.

Coronelli designed the globe to make the observer feel as though they were looking into the sky from earth. The engraving is incredibly detailed with the names of the constellations written in Latin, Italian, French, Greek, Arabic. Comets are included with little circles of stars and the dates when they appeared. Despite the elegant and accomplished production, Coronelli’s lack of attention to scientific details places it as both a high point and low point of globe production in the late 17th century.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, a time of immense public interest in exploration, voyage tracks became a popular feature on globes and a key selling point emphasised by globemakers. The globe by Palmer & Newton is one of the earliest to record all three of Cook’s voyages, showing the complete tracks of his first two voyages and marking the places his third voyage visited.

Larger globes like these, designed for placement on desks, tables or floors, were as much intended for display — to convey the wealth and worldliness of their owner — as they were for use in instruction or reference.

![A new terrestrial globe on which the tracts and discoveries are laid down from the accurate observations made by Captains Cook, Furneux [sic], Phipps … 1782 by William Palmer & John Newton](https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/e43703_0006.jpg?itok=YKst0Ohf)

![A new terrestrial globe on which the tracts and discoveries are laid down from the accurate observations made by Captains Cook, Furneux [sic], Phipps … 1782 by William Palmer & John Newton](https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/e43703_0006.jpg)