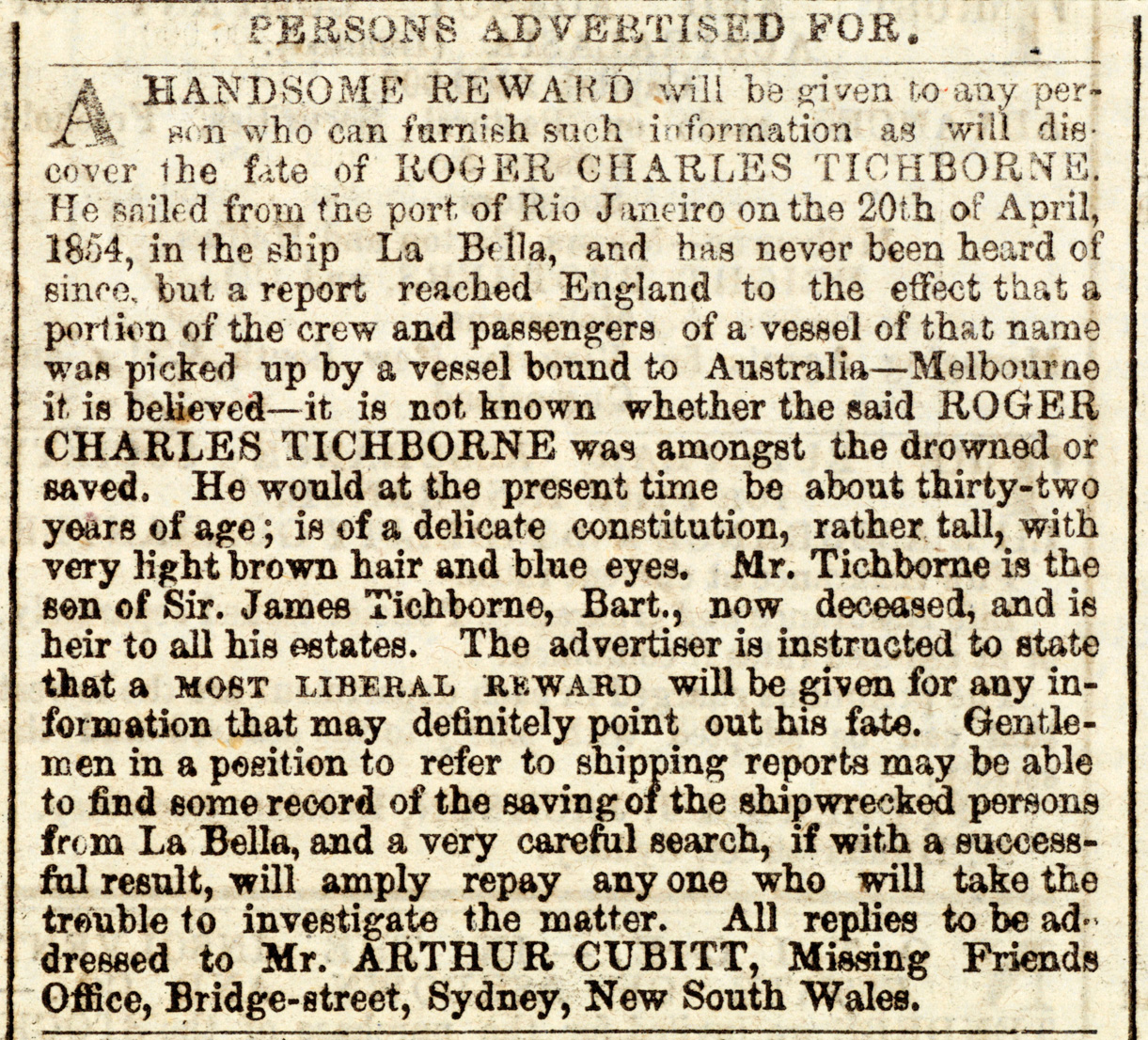

Castro visited the family estates and met various people who had known Sir Roger. He managed to acquire some powerful allies, including the Tichbornes’ solicitor, Edward Hopkins, and Andrew Bogle, a servant of Sir Roger’s uncle.

A few weeks later, he went to France to meet Lady Tichborne. It didn’t take much to convince her that this was her son back from the dead. A number of other family members also welcomed him back into the fold. Lady Tichborne set the Wagga Wagga butcher up in England, and gave him plenty of money to live on. By spending time with the family and picking their brains, he managed to thoroughly research Sir Roger’s life and maintain the deception, at least as far as some people were concerned.

Others were not so convinced. They discovered, through an agent in Australia, that Tom Castro was, in fact, Arthur Orton, who had been born in London. He made his way to Australia, but jumped ship for a while and spent time in Chile – as he’d actually been in South America, he was able to talk very convincingly to Lady Tichborne about it.

One serious mistake Orton made was to contact his real family in Wapping, East London, when he arrived back in England – something the sceptical members of the Tichborne family later discovered.

Even after Lady Tichborne died in 1868, Orton kept up the pretence, as he’d run up large debts that needed to be paid off. No longer having to worry about what Lady Tichborne thought, certain members of the family took him to court over his claim. This became one of the most famous legal cases of the nineteenth century, providing an enormous amount of entertainment to the general public, with the population divided into supporters and sceptics.

The first trial lasted nearly a year, from 11 May 1871 to 5 March 1872. Tichborne v. Lushington was a civil trial to establish Orton’s claim to the Tichborne inheritance, and to eject the tenant, Colonel Lushington, from the family estate. Almost 100 people spoke in Orton’s defence, but the main stumbling block in his story was his inability to speak French which, of course, Sir Roger spoke fluently.

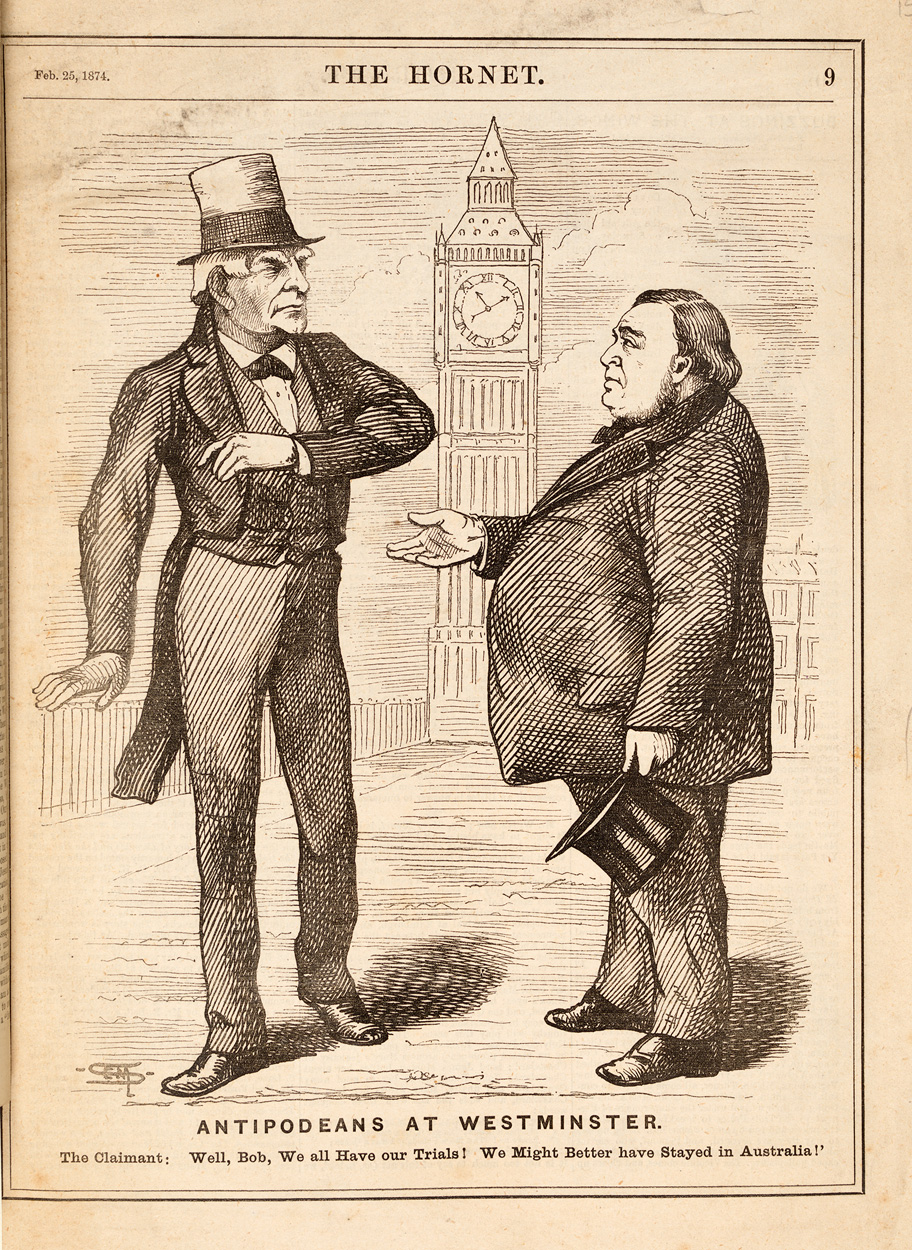

Arthur Orton’s perjury trial, Regina v. Castro, began in 1873 and went on for more than six months. A jury had to be convinced that Orton’s claim to be Sir Roger Tichborne was false. They didn’t need much convincing – in February 1874, he was convicted of two counts of perjury and sentenced to 14 years’ hard labour by Lord Chief Justice Sir Alexander Cockburn.

Soon after the trial, Orton’s defence lawyer, Edward Kenealy, was elected to parliament and unsuccessfully tried to have the Tichborne case examined by a Royal Commission.

Orton served 10 years in prison, getting out in 1884. Although he confessed once, in 1895, to being an impostor, he later withdrew that. Life after jail was rough – without access to the Tichborne fortune, he lived in poverty and was destitute by the time of his death.

Strangely, after Orton died in London in 1898, he was officially acknowledged as Sir Roger Tichborne: his death certificate and coffin plate both bare this name. The London Daily Mail said:

"The Judges of the High Court were two years in determining that the living Tichborne was Orton. The Registrar of Births and Deaths determined in two minutes that the dead Orton was Tichborne."

Press reaction to the Tichborne case

The press had a field day with the Tichborne case – the whole thing was so unlikely that it made for a hilarious yarn, and one that the press could mercilessly send up.

The library has a significant collection of material relating to the case, including these three comics, numbered two, eight and nine in a humorous series called Clarke’s Whims and Oddities, published by H.G. Clarke & Co. in London’s Covent Garden. These little pamphlets folded out into a single sheet containing ‘a humorous poem, with 16 droll illustrations’, and were available in plain or coloured editions, for one penny or sixpence. The interest in the trial spawned thousands of similar cheap, popular publications, as well as broadside ballads.