Just ten years ago, the Southern Cross was the most popular tattoo design in Australia. Today it is the tattoo most commonly being removed. National symbols never stand still.

We often think of nations as transcending history, as permanent fixtures dating back to time immemorial. But the nation-state is a relatively new phenomenon, emerging in the American and French revolutions to slowly displace military empires and dynastic regimes. The symbols through which we imagine the nation are constantly changing, despite the desire to think of them too as immovable.

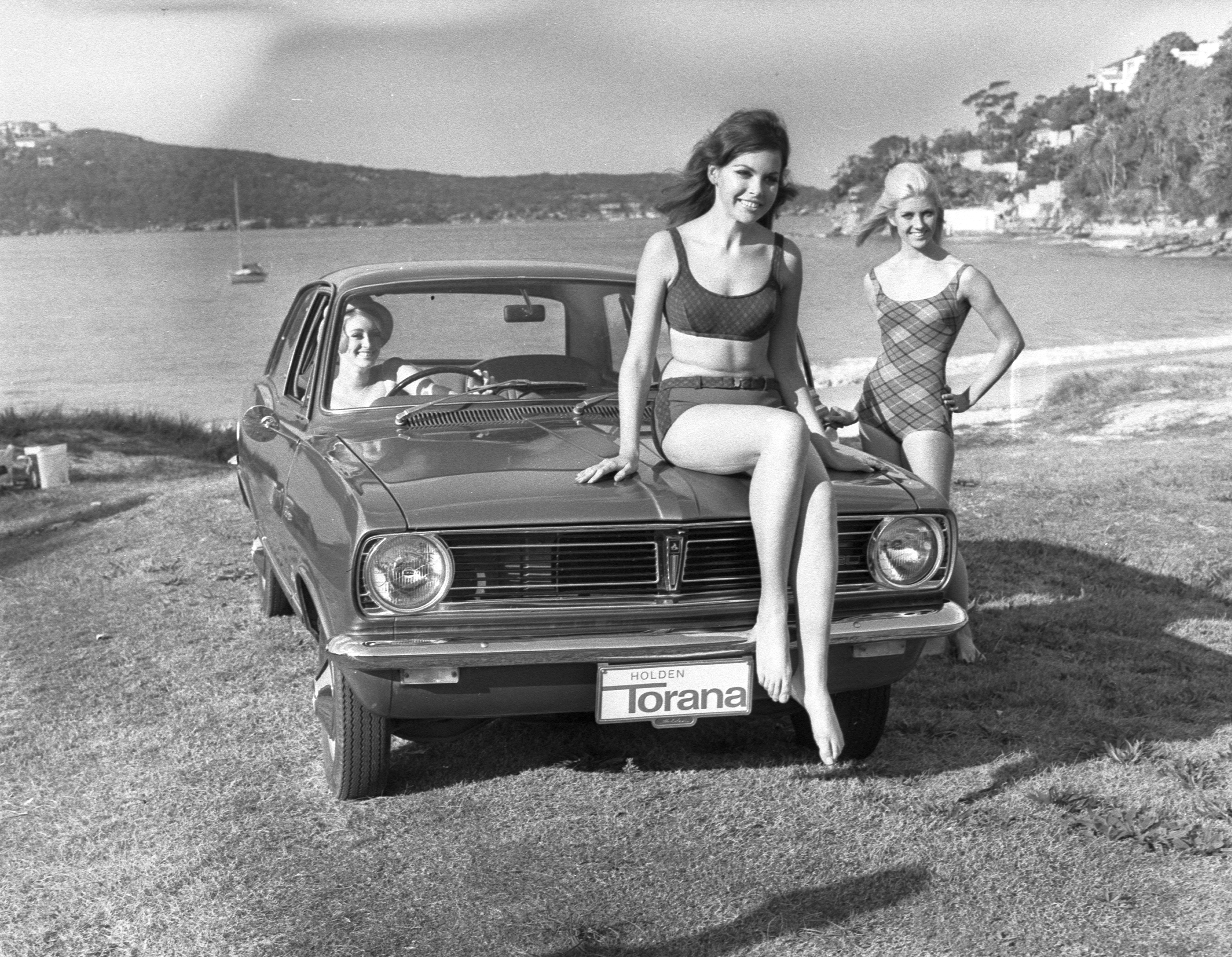

The mutability of national symbols and the rapidity with which they change was brought home to the 30 of us working on a new edition of Symbols of Australia, first published in 2010. Even during the four years of editing and updating, it was hard to keep up as well-established national symbols shifted on their foundations. The Holden — Australia’s own car, a symbol of industrial maturity and a fixture of post-war consumer culture — came to the end of the road in 2017. The last Holden became a museum piece, as had the first Holden prototype.

Uluru’s role as the symbolic heart of the nation was elevated further: ant-trails of tourists no longer scramble over its surface and the Uluru Statement from the Heart has the potential to change fundamental relationships at the core of the national polity.

And then, there’s the Akubra. It seemed a fixture on prime ministerial pates whenever a bush photo-op beckoned. Like so many invented traditions, that habit was itself of recent lineage — can you imagine Menzies or Whitlam in an Akubra? But in 2018 on his first day as prime minister Scott Morrison joked, ‘I don’t have an Akubra, mate’ when discussing the drought. On his first prime ministerial trip to see its impact in Queensland, he ostentatiously wore a baseball cap.

Even the formal symbols of nation can be surprisingly flighty, changing not only their meaning but their very appearance. The Howard government passed legislation in 1998 to make it harder to alter the national flag. But the flag it sought to protect from change had only formally become the national flag in 1954. Until then, the flag that had precedence over all other flags in Australia was the Union Jack. Even in World War II, families had to seek permission, which was always given, to drape a soldier’s coffin with an Australian ensign. Menzies, British to the bootstraps, changed the order of precedence without ever admitting it.

A more recent innovation, ‘Australian National Flag Day’, proclaimed in 1996, commemorates the day the blue ensign was first flown, 3 September 1901. It was not the national flag but one of two shipping ensigns, blue for Commonwealth government use and red — sometimes known as ‘the people’s flag’ — for merchant ships. And that 1901 flag design was tweaked before being sent for final approval to the British Admiralty, which tweaked it again before it was gazetted in 1903. It was changed yet again in 1908 when the Commonwealth Star acquired a seventh point. Australians found their flag a puzzle for another 50 years.

Perhaps they still do. Among so-called sovereign citizens, the red ‘people’s flag’ has re-emerged as a symbol of protest at various anti-vax rallies during 2021. This conveniently glosses over the suggestion that Menzies preferred the blue ensign in the 1950s because red was the colour associated with communism.

The Australian coat of arms had an even rockier road. Granted by King Edward VII in 1908, the first arms had the familiar kangaroo and emu supporting the English cross of St George at the centre. But with no St Andrew’s or St Patrick’s cross, Scotsand Irish-Australians were outraged. The whole design went back to the drawing board and a new coat of arms was proclaimed in 1912. In 1954 — a year of symbol renovation perhaps, with the excitement of a ‘new Elizabethan Age’ and a royal visit — the government decided the 1912 coat of arms looked a bit dated. A design by Eileen Mayo was chosen — she introduced both a crown and a stylised Aboriginal shield into the mix — but nothing more came of it as the whole enterprise ran out of money. The 1912 version survived.

Another item formally listed as a national symbol — to be sung rather than seen — is the national anthem. It too has a chequered history. ‘God Save the Queen’ was the national anthem in 1901, though ‘Advance Australia Fair’ was also sung at the inauguration of the Commonwealth. Its original 1878 lyrics were considerably revised for the occasion – we gained ‘boundless plains to share’ but dropped mention of ‘gallant Cook’, ‘sires of yore’ and Britannia ruling the waves. When, after some awkwardness, it was proclaimed the national anthem in 1984, ‘Australians all’ replaced ‘Australia’s sons’ and the oft-forgotten second verse saw further changes. In 2021, ‘young and free’ became ‘one and free’.

Australia’s floral emblem — the golden wattle (acacia pycnantha Benth.) — was only proclaimed in 1988 and National Wattle Day (1 September) formally recognised in 1992. However Wattle Day Leagues had long been out celebrating on various dates in a number of states. The wattle was already popular as a national symbol — though not without some occasionally acrimonious dissent from advocates of the waratah. Team Waratah thought its deep red colour and shapeliness made it a more decorative choice. In any case acacias were found elsewhere — diplomatic spats erupted when South Africa used acacia for symbolic purposes.

The wattle won the war. Its jaunty yellow and springtime flowering were commonly seen as representing the cheerfulness and wholesomeness of the new nation (not if you were asthmatic, protested the waratah advocates). Today, according to the prime minister’s departmental website, it is wattle’s ‘resilience’ that ‘represents the spirit of the Australian people’. The cluster of meanings and emotions attached to particular symbols are as changeable as the symbols themselves.

Wattle re-emerged as a symbol of commemoration in 1999 when Governor-General Sir William Deane cast 14 sprigs into the Saxeten Gorge in Switzerland to remember the 14 young Australians killed there in a canyoning accident. Its use commemorating the Bali bombings in 2002 confirmed it in that role, which harked back to earlier elegiac meanings of the wattle which had disappeared as the twentieth century progressed. In Adam Lindsay Gordon’s best-known poem, ‘The Sick Stockrider’, the hero wanted to die, ‘in the hollow where the wattle blossoms wave’. After Gordon shot himself in 1870, Elizabeth Lauder, romantically attached to the poet, planted wattle on his grave and for the next 30 years sent its seeds to Victorian schools to be planted in Gordon’s memory.

Another poet, CJ Dennis, buried his larrikin Anzac hero Ginger Mick under mimosa — the closest thing at hand to wattle — on Gallipoli:

But never was the fairest wattle wreath More golden than the ‘eart uv’ im beneath.

Wattle’s acceptance as a symbol and shifts in meaning suggest that official proclamations are only part of the story. If official symbols, fixed by government regulation, are so unstable, what of those many more national symbols that acquire their significance through everyday usage? Popular culture can be far more capricious — and ruthless. Around Federation, as six colonies of Britain were creating a nation-state and a single protected market, the continent was awash with symbols. Manufacturers packaged and branded more and more products with trademarks emphasising Australianness, taking national symbols into the home. Among hundreds of products with nationally inspired packaging were Kangaroo bicycles, Emu chocolates, Boomerang explosives, Possum wine and Cooee tomato sauce, almost all now consigned to the dustbin of history.

The rising sun was particularly popular around Federation, identifying the newly emerging Australia with the future, distinguishing Australia from older nations whose symbolism seemed preoccupied with the past. In 1901 Australians saw themselves as being ‘in advance’ of the rest of the world, not just because the 1884 agreement on an international dateline meant they were among the first peoples to greet a new day. They also believed their social policies placed them in the vanguard of human progress, relishing their reputation for democracy, egalitarianism and social justice.

So ‘rising sun’ hotels, gold mines, football clubs and fraternal lodges could be found throughout the colonies. The motif often decorated gables of houses in the prevalent architectural style known later as ‘Federation’. It appeared on the New South Wales and South Australian coats of arms of 1906 and 1936 respectively. On Australia House in London the rising sun was represented by Apollo in a dramatic sculpture — assertively facing East — unveiled in 1924. The badge designed for the Australian military forces in 1902, based on an arrangement of swords, became commonly known as ‘the rising sun’. It reminded many of Hoadley’s ‘Rising Sun’ jam.

In 1941, the Australian Women’s Weekly bravely announced, ‘The sun never sets now on the slouch hat and the rising sun badge’, just as it did so. The rising sun’s popularity as an Australian symbol did not survive the war; within six months Japan attacked Pearl Harbor under its own distinctive ‘rising sun’ flag. Fifty years later the Australian defence forces began using it again in their advertising so effectively that now there is little sense that the rising sun might have any national meaning other than a military one.

The conventional nineteenthcentury representation of nations — portrayed in formal settings as well as cartoons — was a Minerva figure along the lines of the UK’s Britannia, the US’s Columbia and France’s Marianne. Australia’s equivalent, ‘Miss Australia’ as she was sometimes called, was often depicted as a daughter of Britannia. A beauty usually depicted in classical dress, she was often surrounded by gum trees, sheep or kangaroos. Often blonde, with wattle in her hair, with a rising sun emphasising her youth, she was always white, pure, virginal. In cartoons, she was the popular stereotype of modern Australian girlhood: pert, opinionated, independent and plucky. A good sport bursting with good health, her tan never compromised her essential whiteness. Whatever her guise, she was something of a male fantasy. But the First World War ended her prominence, as more masculine and martial virtues took precedence. Perhaps too as women began to appear in political life the merely allegorical role no longer suited. From the 1920s, real women vied to be ‘Miss Australia’ in beauty contests. It’s hard to imagine her reappearing as a symbol of Australia today.

The cooee was another symbol that faded through the twentieth century. From early in the nineteenth century, it was accepted as an aural national symbol, like the Swiss yodel, Big Ben’s chimes or the kookaburra’s laugh. One enthusiast, WJ Sowden, urged his compatriots to replace three cheers with three cooees. Another, Maude Wordsworth James, wanted a cooee corner set up in every Australian home, with various cooee knick-knacks, including, perhaps, the cooee cuckoo clock which had an Aboriginal man popping out to cooee on the hour.

Cooee jewellery was also a thing, the word spelt out as a gem-encrusted snake. Cooees were a feature of welcomes to Nellie Melba in 1902, the Great White Fleet in 1908 and Lord Baden Powell in 1912, not to mention Annette Kellermann’s diving exhibitions throughout the world. Football games and theatres rang with cooees as much as the bush was supposed to. Recruitment campaigns from 1914 went to town, enlisting the cooee as the Empire’s call for help to Australia: no cooee could go unanswered. Yet in the more restrained society of the 1920s those exuberant cooees disappeared. The cooee seemed outdated as the nation searched for more modern national symbols such as the surf lifesaver, or the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

The popularity of other symbols has fluctuated considerably over two centuries of use. One era’s daggy embarrassment can turn into another’s fashionable accessory, and vice versa. Some were the height of modernity and sophistication when they first appeared on the symbolic landscape — the lifesaver and the Holden for example — but came to depend on a patina of affectionate nostalgia for their survival. Others that fall out of use for a time return in ironic mode.

The ways symbols come and go are many and varied. Vegemite only began to register as a national symbol with clever advertising in World War II. Uluru gained traction once tourism took off in the 1950s. The billy, once ubiquitous in the bush, is disappearing as bushwalkers make space for their portable espresso maker. The boomerang, a stalwart of Australian symbol-making for two centuries, has less currency as white Australia becomes more conscious of appropriating Indigenous culture.

Other symbols emerge with attempts to find new ways of appropriately reflecting a diverse community. A decade ago, the Rainbow Serpent was a popular national symbol but its trivialisation and overt appropriation saw its retreat. The latest symbol to join the national pantheon — now added to the new edition of the book — is the democracy sausage. It has come to embody the particular character of Australian democracy – or the way Australians like to imagine their democracy.

Other symbols survive but twist their imagined meanings. Two centuries ago the kangaroo represented Australia’s oddity. As the non-Indigenous native-born took control of their own symbol making, it stood for pugnacity or resilience. Now kangaroos are more commonly associated with nature’s fragility in the face of climate change. Even the Qantas kangaroo is subjected to subtle revamps, the latest in 2016.

The symbolism of the Anzac as a representative Australian originally drew on his status as a citizensoldier, a casual she’ll-be-right larrikinism that held military authority in contempt. Now it has come to serve the needs of a professional regular army. With no original Anzacs left to protest, Anzackery has become the plaything of politicians and the military.

Perhaps more significant than these comings and goings is the way the debates around national symbols never stop moving on. Our thinking about national symbols in 2010 seems almost quaint compared to how we think about national identity in the 2020s, as new voices come to the fore and Australia’s place in the world shifts. Yet the history of national symbols is not only fascinating, quirky and unexpected; their history reveals a great deal about where ‘we’ have come from and how ‘we’ have imagined ourselves. Perhaps even how ‘we’ can look to the future. And that raises a fundamental point: who is this ‘we’? Symbols attempt the impossible in defining ‘us’. Whoever we are.

Richard White is a historian, and is co-editor, with Melissa Harper, of Symbols of Australia: Imagining a Nation (NewSouth, 2021).

This story appears in Openbook summer 2021.

Openbook

Openbook is for people who love to read.

Strike me pink!

Has news of the demise of Australian English been greatly exaggerated?

When newspapers took over Australian television

The machinations behind the first Australian television licences.

Daring and devotion

The art of Sydney couple George and Charis Schwarz defies neat categories, but their body of work will be preserved.