Ulladulla snapper fisherman, 1959, by Jeff Carter, PXD 1070 © Jeff Carter archive

a4186060u

By Dr Ruth Thurstan

"The monthly fishing excursion took place on Saturday after the usual club breakfast at the Exchange. The wide ground of Long Reef was the scene of operations, and it may be safely stated that such a day’s fishing has rarely taken place so near Sydney Heads. The wind was so strong that the steamer was constantly drifting off the ground, so that the fishing-proper may be confined to about two hours, during which over four hundred schnapper were caught. The fish were so thick that one gentleman, having his line mounted with two hooks, caught eight good sized fish in four consecutive casts."

This description from the Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser in 1875 is one of many references to the increasingly popular contemporary pastime of fishing for snapper (Chrysophrys auratus), known back then as ‘schnapper’. Snapper occur throughout Australia’s sub-tropical and temperate coastal waters, and form part of the sea bream family, Sparidae. Snapper Fishing Off Sydney Heads, from the Sydney Mail, 26 August 1893, p. 340

Snapper fishing was not new in the 1870s — archaeological and historical evidence shows that Indigenous people ate snapper prior to the arrival of Europeans. During the late nineteenth century, however, interest in this species surged as steam power enabled offshore fishing grounds to be routinely exploited for the first time.

Areas where snapper were abundant became known as ‘schnapper grounds’. Many of the earliest fishers to exploit these grounds were recreational rather than commercial fishers, with articles joking about the amateurs’ sea-sickness. In 1900, the Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate reported:

The local Schnapper Fishing Club had a very successful outing to Broughton Island the other day in the steamer Swansea and had a splendid haul of fish, some 350 schnapper and about the same quantity of other fish being caught. The members of the club speak highly of Captain Hannell for the attention he paid to excursionists and in finding a good fishing ground for them. It is the intention of the club to make another trip soon.

As a marine biologist with an interest in how fish populations have changed over time, I have been using the Library’s archives to explore these late nineteenth and early twentieth century fishing grounds. Drawing information from government annual reports, royal commission evidence and popular media, including metropolitan and regional newspapers, I am using this historical data to help understand the magnitude of change in our coastal marine environments.

Understanding how natural environments have changed, and what drives these changes, requires years of scientific observation. When it comes to oceans and the animals within them, observing change isn’t straightforward. Even with scuba gear and underwater cameras, we know relatively little about what marine communities look like today, and we know even less about what they looked like in the past.

During the past 120 years or so, our impact on marine environments has increased dramatically. Industrialisation has intensified fishing, agriculture and coastal development, depleting fish populations, and increasing silt loading and pollution.

Today, snapper is fished commercially and is also popular with recreational fishers. Along the east coast, there are concerns about the declining snapper population, but long-term trends are difficult to determine with only a few decades of fisheries data. In the archives, I found a huge amount of information about early fishing trips, snapper abundance and nineteenth century fishing culture. Many accounts include the level of detail reported in the Evening News in 1877:

About forty members of the Nimrod Club went out for a day’s sport on Thursday in the steamer Breadalbane and caught 1,012 fish. The spot at which most of the fish were caught was off Coogee, where the fish bit freely, and were hauled in very rapidly sometimes two and three at a time. A whale was also seen sporting about. The sport lasted till five o’clock, when the Breadalbane steamed for home.

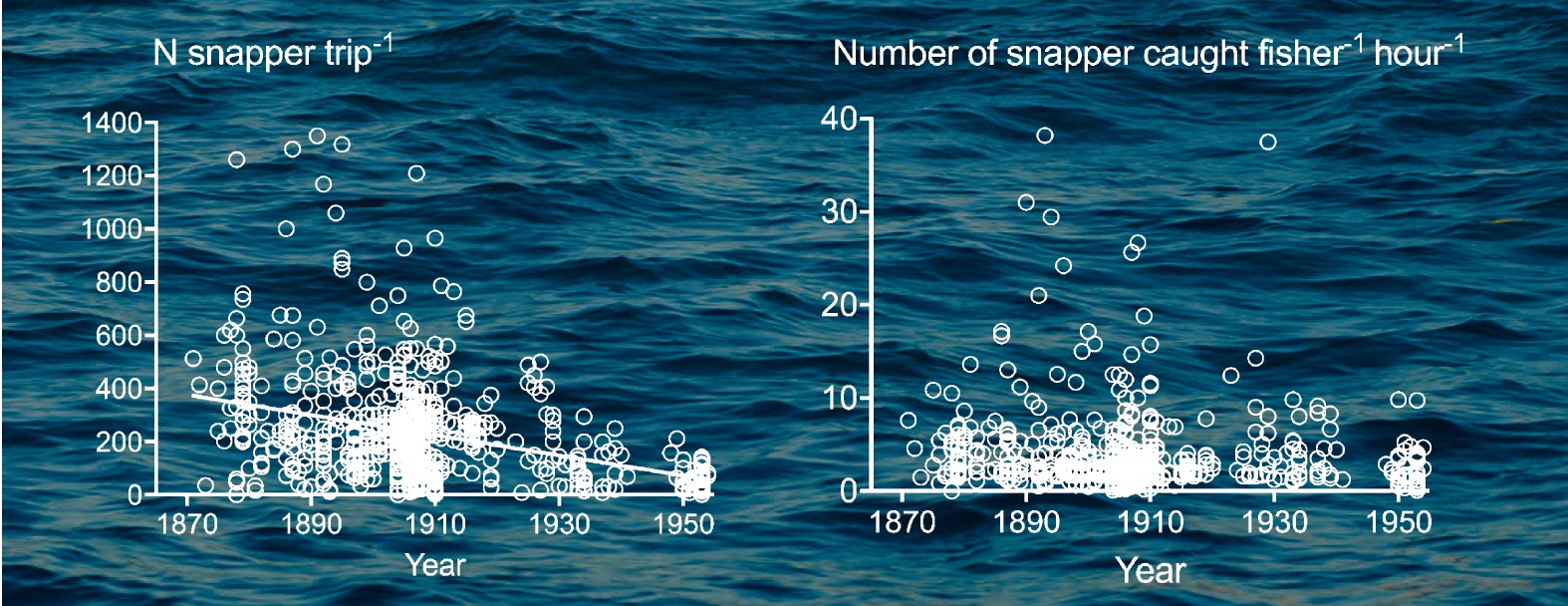

Historical data allows us to track the number of snapper caught per fisher per trip, and the number of snapper caught per fisher per hour, by amateur fishing parties from south Queensland and New South Wales between 1871 and 1954. In the early days, large steamer vessels would carry between eight and 30 people per trip, returning with snapper in the hundreds and occasionally over 1000. Over time, catches per boat got smaller as large steamers were replaced by smaller motorboats, although the catch of snapper per fisher per hour did not change significantly from the 1870s to the 1950s.

These graphs of quantitative data collated from the archives show the number of snapper caught per fisher per trip, and the number of snapper caught per fisher per hour. The trips all recorded the catch of amateur fishing parties from south Queensland and NSW between 1871 and 1954.

There is ample evidence, however, that in later years boats needed to travel further from the major population centres to maintain their catch rates. Decline in abundance in inshore waters has been observed since the nineteenth century, for example in a royal commission report from 1880:

20 and 30 dozen count fish were often taken by two fishermen on [the Broken Bay] grounds. Now, however, the […] grounds about Broken Bay have fallen off in their productiveness to an alarming degree.

Interpreting trends in fishing catches is not without problems. Data is missing from many records, and there may have been biases in reporting. Were only the best catches reported, giving us a skewed picture of fishing productivity? Statistical analyses can help fill in gaps, while comparison with alternative data sources such as government surveys can help determine the extent of bias in popular records.

Another challenge is comparing historical and contemporary experiences. After the 1960s, newspaper reports on fish catches are scarcer, partly because fewer recent newspapers have been made available online, but also due to cultural changes in recreational fishing. Snapper fishing became less newsworthy as more people had boats, while fishing magazines began to replace newspapers for reporting catches. In more recent decades, growing concerns about the environment meant reports of large catches were no longer acceptable. To address this dearth of recent evidence, I am interviewing long-term fishers and exploring online sources such as social media.

Historical sources like those in the Library are an exceptional opportunity to record fishing activity from a time when scientific monitoring was limited. In providing a long-term perspective, we can use history to help inform contemporary understanding about how humans have influenced fisheries and the wider marine environment.

Dr Ruth Thurstan is the Alfred Deakin Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Deakin University, Victoria, and was the Library’s 2015 David Scott Mitchell Memorial Fellow.