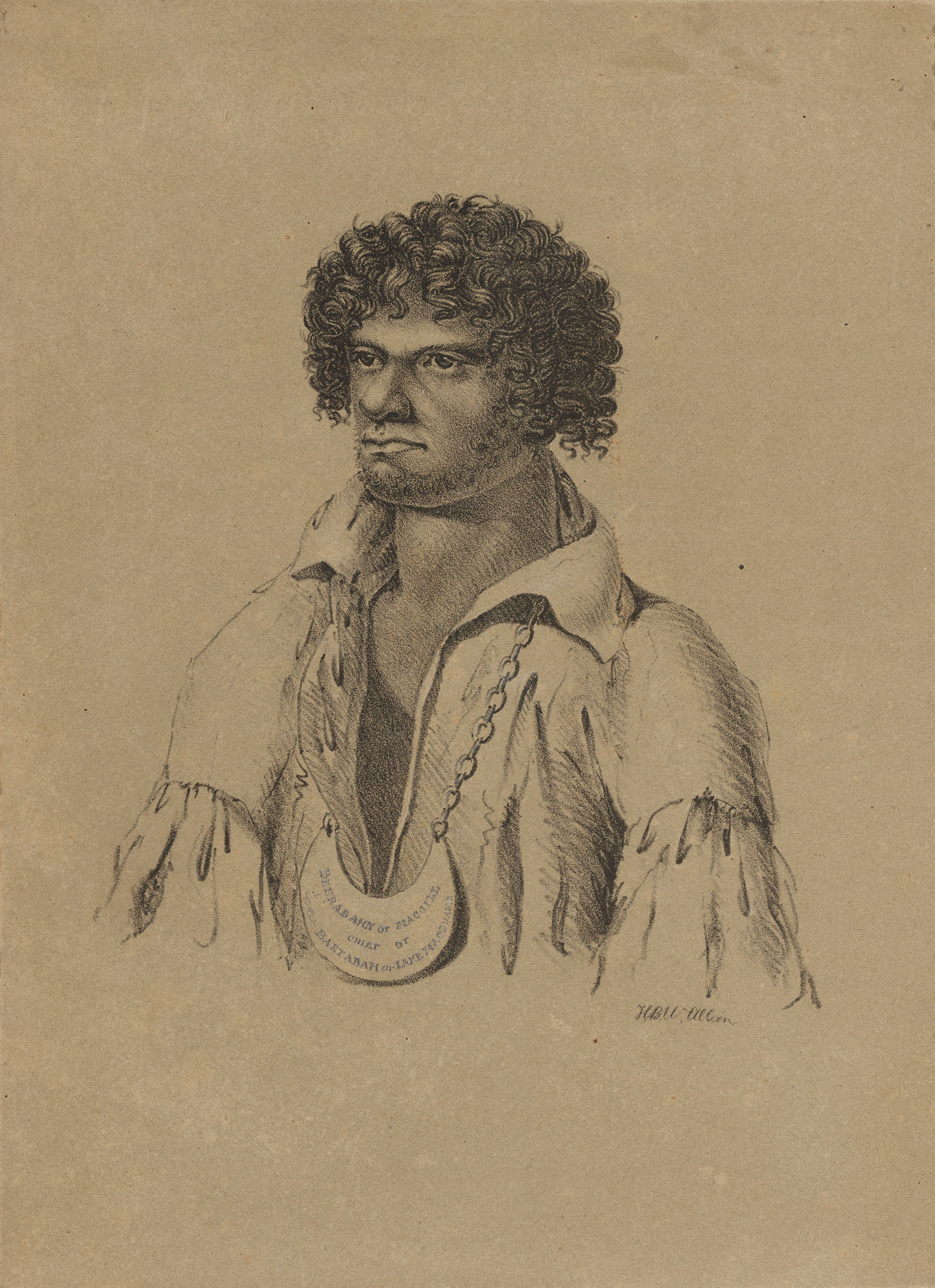

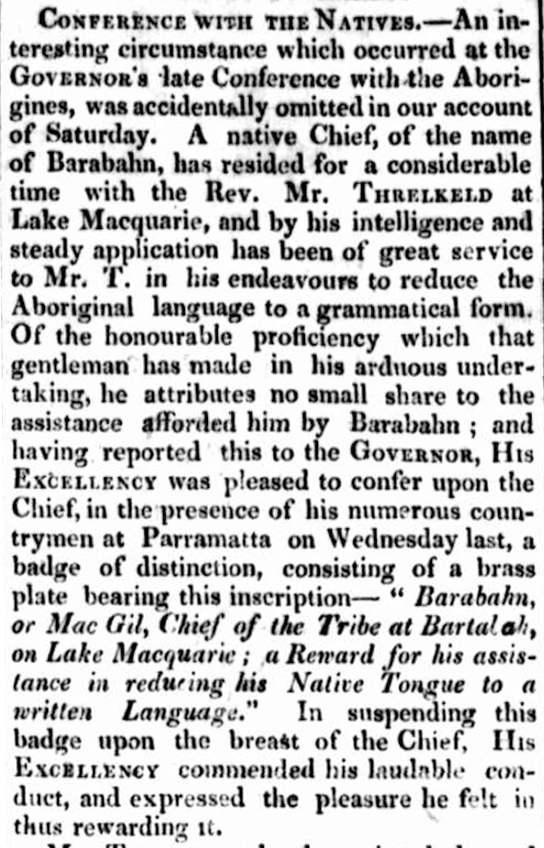

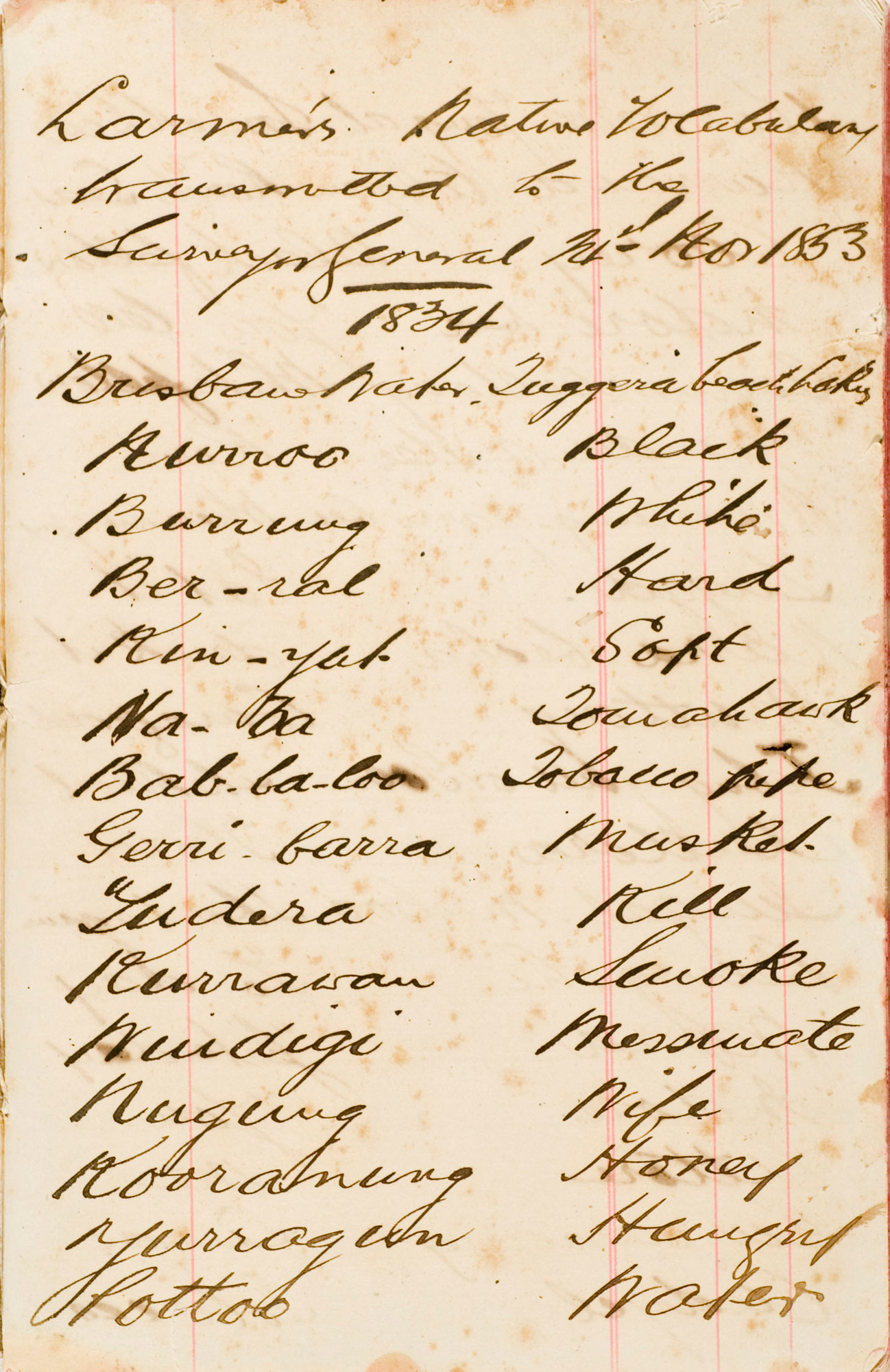

Beerabahn or MacGill, Chief of Bartabah or Lake Macquarie, c 1830

{"type":"image","clickUrl":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/collection-items\/beerabahn-or-macgill-chief-bartabah-or-lake-macquarie","thumbnail":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/thumbnail\/public\/e17333_0001_c_web.jpg?itok=mu-HRNAv","thumbnailLarge":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/large\/public\/e17333_0001_c_web.jpg?itok=ml-CmTTB","mediaDerivativeUrls":{"thumbnail":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/thumbnail\/public\/e17333_0001_c_web.jpg?itok=mu-HRNAv","large":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/large\/public\/e17333_0001_c_web.jpg?itok=ml-CmTTB","responsive__quarter_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__quarter_hd\/public\/e17333_0001_c_web.jpg?itok=uKqXsQpQ","responsive__half_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__half_hd\/public\/e17333_0001_c_web.jpg?itok=CDQMn1mi","responsive__full_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__full_hd\/public\/e17333_0001_c_web.jpg?itok=ThFcX5-b"},"mediaUrl":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/e17333_0001_c_web.jpg","mediaMime":"image\/jpeg","transcriptUrl":null,"width":1453,"height":2001}

View collection item detaile17333_0001_c