To mark the progress of the seasons, as the days become shorter and the temperature cools, we take a look at some trees in the Library's collection.

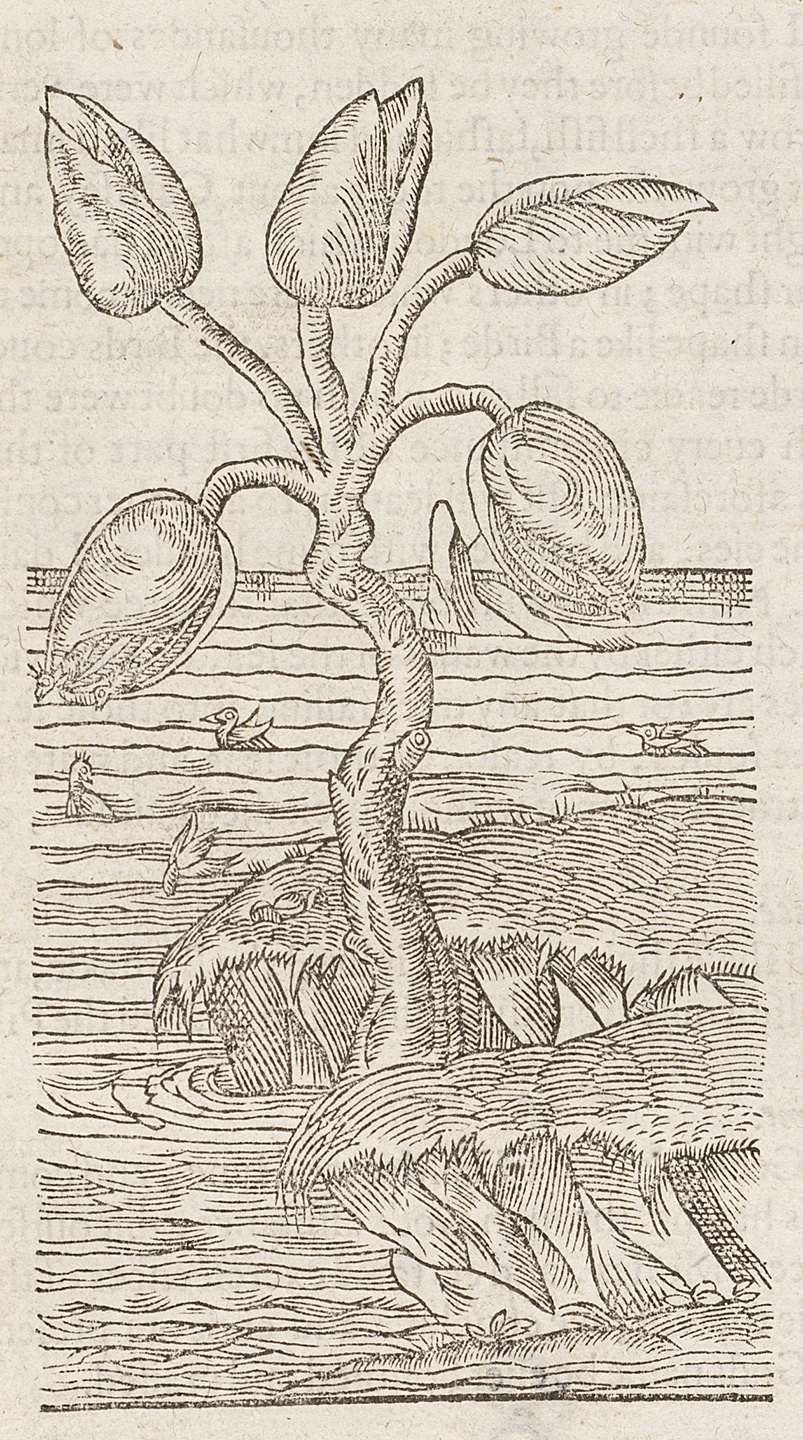

The Herball, or Generall Histories of Plantes, gathered by John Gerarde, Imprinted at London by John Norton, 1597

{"type":"image","clickUrl":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/collection-items\/herball-or-generall-histories-plantes","thumbnail":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/thumbnail\/public\/v1-fl3743755_crop.jpg?itok=ZwUQ4CL6","thumbnailLarge":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/large\/public\/v1-fl3743755_crop.jpg?itok=cWwpk6nQ","mediaDerivativeUrls":{"thumbnail":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/thumbnail\/public\/v1-fl3743755_crop.jpg?itok=ZwUQ4CL6","large":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/large\/public\/v1-fl3743755_crop.jpg?itok=cWwpk6nQ","responsive__quarter_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__quarter_hd\/public\/v1-fl3743755_crop.jpg?itok=2W0EbiuA","responsive__half_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__half_hd\/public\/v1-fl3743755_crop.jpg?itok=nGw9X0Bk","responsive__full_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__full_hd\/public\/v1-fl3743755_crop.jpg?itok=d_zhF0Cq"},"mediaUrl":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/v1-fl3743755_crop.jpg","mediaMime":"image\/jpeg","transcriptUrl":null,"width":803,"height":1440}

View collection item detail

{"type":"image","clickUrl":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/collection-items\/herball-or-generall-histories-plantes","thumbnail":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/thumbnail\/public\/v1-fl3743755_crop.jpg?itok=ZwUQ4CL6","thumbnailLarge":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/large\/public\/v1-fl3743755_crop.jpg?itok=cWwpk6nQ","mediaDerivativeUrls":{"thumbnail":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/thumbnail\/public\/v1-fl3743755_crop.jpg?itok=ZwUQ4CL6","large":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/large\/public\/v1-fl3743755_crop.jpg?itok=cWwpk6nQ","responsive__quarter_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__quarter_hd\/public\/v1-fl3743755_crop.jpg?itok=2W0EbiuA","responsive__half_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__half_hd\/public\/v1-fl3743755_crop.jpg?itok=nGw9X0Bk","responsive__full_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__full_hd\/public\/v1-fl3743755_crop.jpg?itok=d_zhF0Cq"},"mediaUrl":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/v1-fl3743755_crop.jpg","mediaMime":"image\/jpeg","transcriptUrl":null,"width":803,"height":1440}

Mythical

Before bird migration was understood, scholars struggled to explain why some species disappeared as the seasons changed. One bizarre animal fable that persisted for centuries was that of the barnacle goose (Branta leucopsis ). The fact that the goose was never seen to breed gave rise to the myth that it spontaneously generated from goose neck barnacles (Lepas anatifera ), a type of crustacean. This biological misunderstanding led naturalists such as John Gerarde, in 1597, to publish misleading observations that the goose formed inside the barnacle shell and came out, legs first, until it hung by its bill, growing feathers once it had fallen into the sea. This legend was finally laid to rest when Dutch sailors saw the birds pairing, nesting and laying eggs.

Taphoglyph from near Dubbo, 1910s, Henry King Photo, Sydney

{"type":"image","clickUrl":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/collection-items\/taphoglyph-near-dubbo","thumbnail":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/thumbnail\/slnswrosetta\/FL224363?itok=sCI9DlqT","thumbnailLarge":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/large\/slnswrosetta\/FL224363?itok=4o-9ldof","mediaDerivativeUrls":{"thumbnail":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/thumbnail\/slnswrosetta\/FL224363?itok=sCI9DlqT","large":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/large\/slnswrosetta\/FL224363?itok=4o-9ldof","responsive__quarter_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__quarter_hd\/slnswrosetta\/FL224363?itok=aiY03H9U","responsive__half_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__half_hd\/slnswrosetta\/FL224363?itok=QqXDEOz3","responsive__full_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__full_hd\/slnswrosetta\/FL224363?itok=aSWe61WW"},"mediaUrl":"https:\/\/digital.sl.nsw.gov.au\/delivery\/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=FL224363&dps_func=stream","mediaMime":"image\/jpeg","transcriptUrl":null,"width":"836","height":"1050"}

View collection item detail

{"type":"image","clickUrl":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/collection-items\/taphoglyph-near-dubbo","thumbnail":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/thumbnail\/slnswrosetta\/FL224363?itok=sCI9DlqT","thumbnailLarge":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/large\/slnswrosetta\/FL224363?itok=4o-9ldof","mediaDerivativeUrls":{"thumbnail":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/thumbnail\/slnswrosetta\/FL224363?itok=sCI9DlqT","large":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/large\/slnswrosetta\/FL224363?itok=4o-9ldof","responsive__quarter_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__quarter_hd\/slnswrosetta\/FL224363?itok=aiY03H9U","responsive__half_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__half_hd\/slnswrosetta\/FL224363?itok=QqXDEOz3","responsive__full_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__full_hd\/slnswrosetta\/FL224363?itok=aSWe61WW"},"mediaUrl":"https:\/\/digital.sl.nsw.gov.au\/delivery\/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=FL224363&dps_func=stream","mediaMime":"image\/jpeg","transcriptUrl":null,"width":"836","height":"1050"}

Cultural

Taphoglyphs, Aboriginal carved trees, can be found dotted throughout Australia but particularly in New South Wales. Specifically the work of Kamilaroi and Wiradjuri artists, Aboriginal people have ceremoniously carved trees as a form of artistic and cultural expression for thousands of years. The Kamilaroi people in the central north-west designed their tree carvings around powerful symbols used for initiation ceremonies, while the Wiradjuri people of central NSW carved trees to mark burial sites of important male elders. Each tree is unique; the majority are geometric in shape and feature chevrons, curvilinear lines, scrolls and concentric circles. Traditionally carved using stone tools, they display strength, skill and artistry.

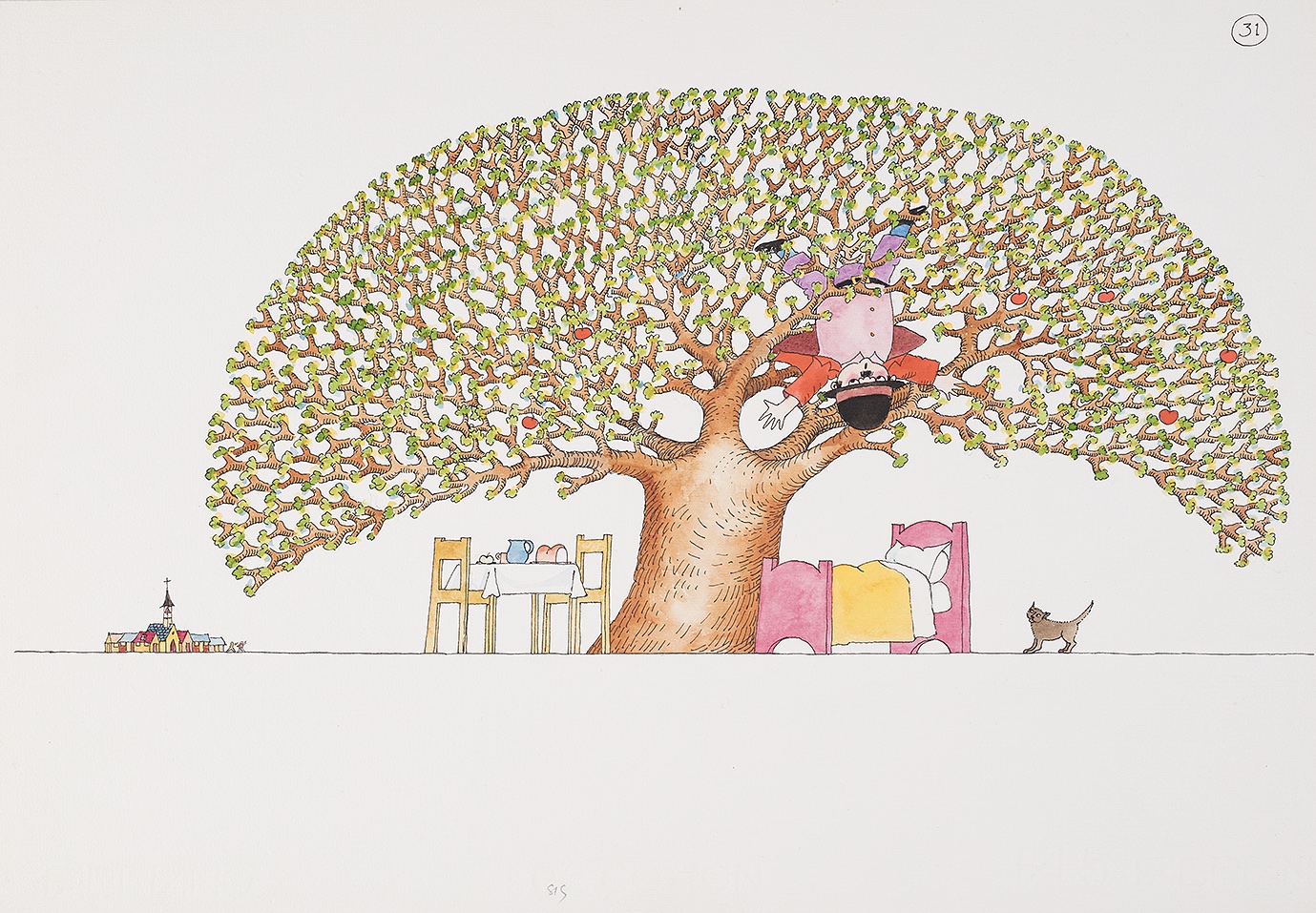

Watercolour for the children’s book Mr McGee, c 1987, by Pamela Allen

{"type":"image","clickUrl":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/collection-items\/watercolour-childrens-book-mr-mcgee","thumbnail":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/thumbnail\/public\/pamelaallen_0002.jpg?itok=i-MSArE3","thumbnailLarge":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/large\/public\/pamelaallen_0002.jpg?itok=An_xOLaI","mediaDerivativeUrls":{"thumbnail":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/thumbnail\/public\/pamelaallen_0002.jpg?itok=i-MSArE3","large":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/large\/public\/pamelaallen_0002.jpg?itok=An_xOLaI","responsive__quarter_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__quarter_hd\/public\/pamelaallen_0002.jpg?itok=UBVh2JCM","responsive__half_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__half_hd\/public\/pamelaallen_0002.jpg?itok=KV9arn3W","responsive__full_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__full_hd\/public\/pamelaallen_0002.jpg?itok=rJ0DpcFu"},"mediaUrl":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/pamelaallen_0002.jpg","mediaMime":"image\/jpeg","transcriptUrl":null,"width":1379,"height":957}

View collection item detail

{"type":"image","clickUrl":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/collection-items\/watercolour-childrens-book-mr-mcgee","thumbnail":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/thumbnail\/public\/pamelaallen_0002.jpg?itok=i-MSArE3","thumbnailLarge":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/large\/public\/pamelaallen_0002.jpg?itok=An_xOLaI","mediaDerivativeUrls":{"thumbnail":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/thumbnail\/public\/pamelaallen_0002.jpg?itok=i-MSArE3","large":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/large\/public\/pamelaallen_0002.jpg?itok=An_xOLaI","responsive__quarter_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__quarter_hd\/public\/pamelaallen_0002.jpg?itok=UBVh2JCM","responsive__half_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__half_hd\/public\/pamelaallen_0002.jpg?itok=KV9arn3W","responsive__full_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__full_hd\/public\/pamelaallen_0002.jpg?itok=rJ0DpcFu"},"mediaUrl":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/pamelaallen_0002.jpg","mediaMime":"image\/jpeg","transcriptUrl":null,"width":1379,"height":957}

Whimsical

‘Mr McGee lived under a tree’… so starts the enduringly popular tale by awardwinning children’s book author and illustrator Pamela Allen. Designed to be read aloud, with short and simple rhyming text, the book is based on the notion that everyone wonders what it might be like to float about in the sky. This intricate watercolour is the secondlast drawing in the story. Set on a clean white page, it shows an inflated Mr McGee just after he has popped and his tumbling descent has landed him safely back in the branches of the tree where he lives. Mr McGee went on to feature in seven more of Allen’s books which have delighted children for more than 40 years. The Library acquired Pamela Allen’s archive in 2020.

Autumn leaves: Maple Tree in Gullick family garden, Killara, c 1918, autochrome plate photographed by William Applegate Gullick

{"type":"image","clickUrl":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/collection-items\/autumn-leaves-maple-tree-gullick-family-garden-killara","thumbnail":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/thumbnail\/slnswrosetta\/FL1016883?itok=U5Nx_18h","thumbnailLarge":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/large\/slnswrosetta\/FL1016883?itok=IriJBldO","mediaDerivativeUrls":{"thumbnail":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/thumbnail\/slnswrosetta\/FL1016883?itok=U5Nx_18h","large":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/large\/slnswrosetta\/FL1016883?itok=IriJBldO","responsive__quarter_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__quarter_hd\/slnswrosetta\/FL1016883?itok=zH0DRjqK","responsive__half_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__half_hd\/slnswrosetta\/FL1016883?itok=K71mdvTR","responsive__full_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__full_hd\/slnswrosetta\/FL1016883?itok=rGWprOdp"},"mediaUrl":"https:\/\/digital.sl.nsw.gov.au\/delivery\/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=FL1016883&dps_func=stream","mediaMime":"image\/jpeg","transcriptUrl":null,"width":"802","height":"1050"}

View collection item detail

{"type":"image","clickUrl":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/collection-items\/autumn-leaves-maple-tree-gullick-family-garden-killara","thumbnail":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/thumbnail\/slnswrosetta\/FL1016883?itok=U5Nx_18h","thumbnailLarge":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/large\/slnswrosetta\/FL1016883?itok=IriJBldO","mediaDerivativeUrls":{"thumbnail":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/thumbnail\/slnswrosetta\/FL1016883?itok=U5Nx_18h","large":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/large\/slnswrosetta\/FL1016883?itok=IriJBldO","responsive__quarter_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__quarter_hd\/slnswrosetta\/FL1016883?itok=zH0DRjqK","responsive__half_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__half_hd\/slnswrosetta\/FL1016883?itok=K71mdvTR","responsive__full_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__full_hd\/slnswrosetta\/FL1016883?itok=rGWprOdp"},"mediaUrl":"https:\/\/digital.sl.nsw.gov.au\/delivery\/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=FL1016883&dps_func=stream","mediaMime":"image\/jpeg","transcriptUrl":null,"width":"802","height":"1050"}

Seasonal

NSW Government Printer William Applegate Gullick was a highly skilled amateur photographer and early promoter of colour photography using autochrome plates. Invented by French brothers, Auguste and Louis Lumière, and released in 1907, the autochrome was the first commercially successful colour photography process. Hailed as revolutionary and described as perhaps the most beautiful of all photographic processes, autochromes produced positive colour images on glass plates coated with millions of red, green and blue dyed potato-starch granules. Popular for portraits and botanical studies, Gullick used the autochrome process to photograph his Killara garden to capture the changing colours of autumn leaves.

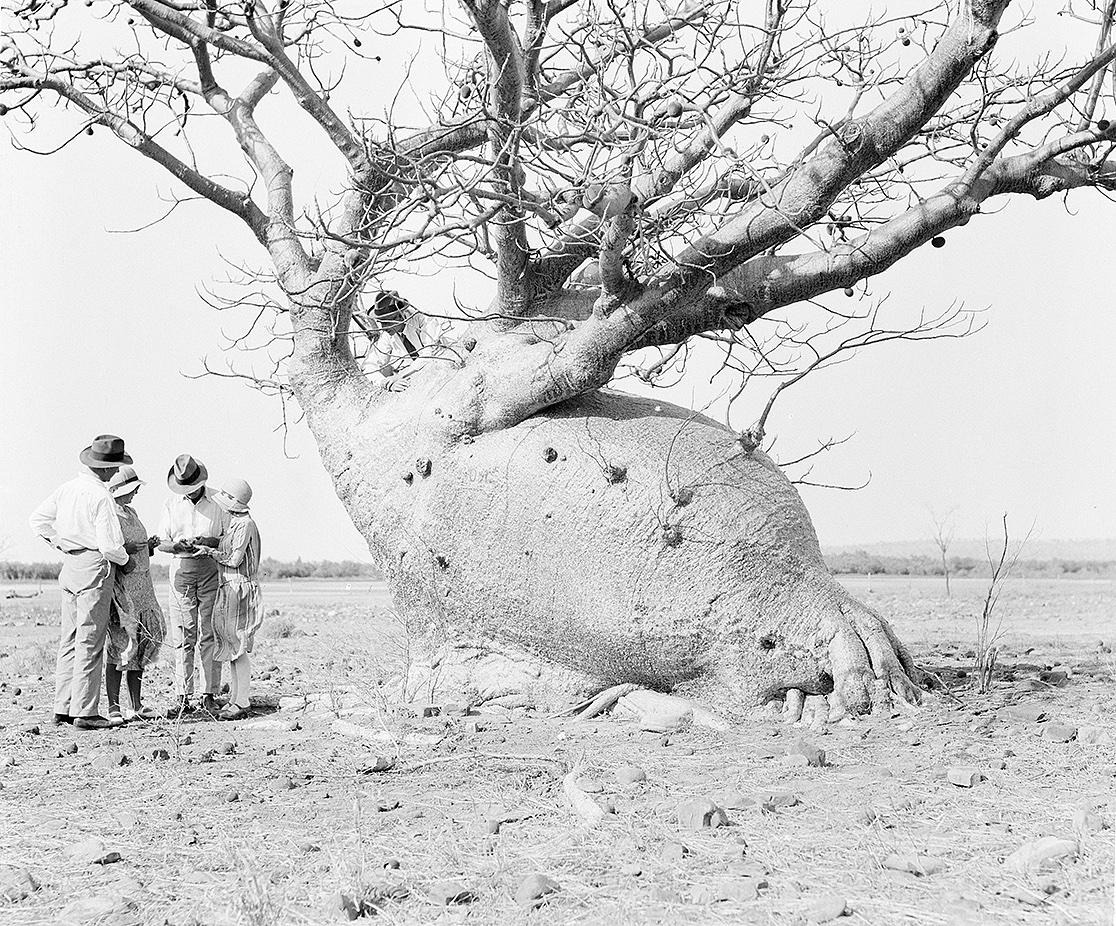

Boab tree, group of men and women, North Western Australia, c 1930, glass plate negative, Australian National Travel Association

{"type":"image","clickUrl":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/collection-items\/boab-tree-group-men-and-women-north-western-australia","thumbnail":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/thumbnail\/public\/v1-fl11881403.jpg?itok=M-xpTxNU","thumbnailLarge":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/large\/public\/v1-fl11881403.jpg?itok=iGQ11qSq","mediaDerivativeUrls":{"thumbnail":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/thumbnail\/public\/v1-fl11881403.jpg?itok=M-xpTxNU","large":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/large\/public\/v1-fl11881403.jpg?itok=iGQ11qSq","responsive__quarter_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__quarter_hd\/public\/v1-fl11881403.jpg?itok=7O8qndR8","responsive__half_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__half_hd\/public\/v1-fl11881403.jpg?itok=r-w_FFAO","responsive__full_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__full_hd\/public\/v1-fl11881403.jpg?itok=ynXjPDec"},"mediaUrl":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/v1-fl11881403.jpg","mediaMime":"image\/jpeg","transcriptUrl":null,"width":1116,"height":926}

View collection item detail

{"type":"image","clickUrl":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/collection-items\/boab-tree-group-men-and-women-north-western-australia","thumbnail":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/thumbnail\/public\/v1-fl11881403.jpg?itok=M-xpTxNU","thumbnailLarge":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/large\/public\/v1-fl11881403.jpg?itok=iGQ11qSq","mediaDerivativeUrls":{"thumbnail":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/thumbnail\/public\/v1-fl11881403.jpg?itok=M-xpTxNU","large":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/large\/public\/v1-fl11881403.jpg?itok=iGQ11qSq","responsive__quarter_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__quarter_hd\/public\/v1-fl11881403.jpg?itok=7O8qndR8","responsive__half_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__half_hd\/public\/v1-fl11881403.jpg?itok=r-w_FFAO","responsive__full_hd":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/responsive__full_hd\/public\/v1-fl11881403.jpg?itok=ynXjPDec"},"mediaUrl":"https:\/\/prod.corp.slnsw.skpr.live\/sites\/default\/files\/v1-fl11881403.jpg","mediaMime":"image\/jpeg","transcriptUrl":null,"width":1116,"height":926}

Botanical

Easily recognised for the large swollen base of its trunk, which gives the tree its bottle-like appearance, the origin of the Australian boab (Adansonia gregorii ) is one of modern botany’s great conundrums. Found in the Northern Territory and the Kimberley region of Western Australia, it lives for hundreds of years and is one of only eight boab species in the world, yet its nearest relatives lie 10,000 kilometres away on the other side of the Indian Ocean. The fruit and flowers of the boab were a traditional food source for local Aboriginal people, while the shell of the boab nut was used for creative expression through carving and storytelling.

Margot Riley , Curator, Research & Discovery.

This story appears in Openbook autumn 2022