Some years ago I was at a conference of international thriller writers (no, I hadn’t known they were a thing either) when a fellow Australian author suggested we visit the New York Public Library in Midtown Manhattan. We had already been to see Grand Central Station and Yankee Stadium, so I had started to wonder if my tour guide wasn’t some kind of weird public-infrastructure buff.

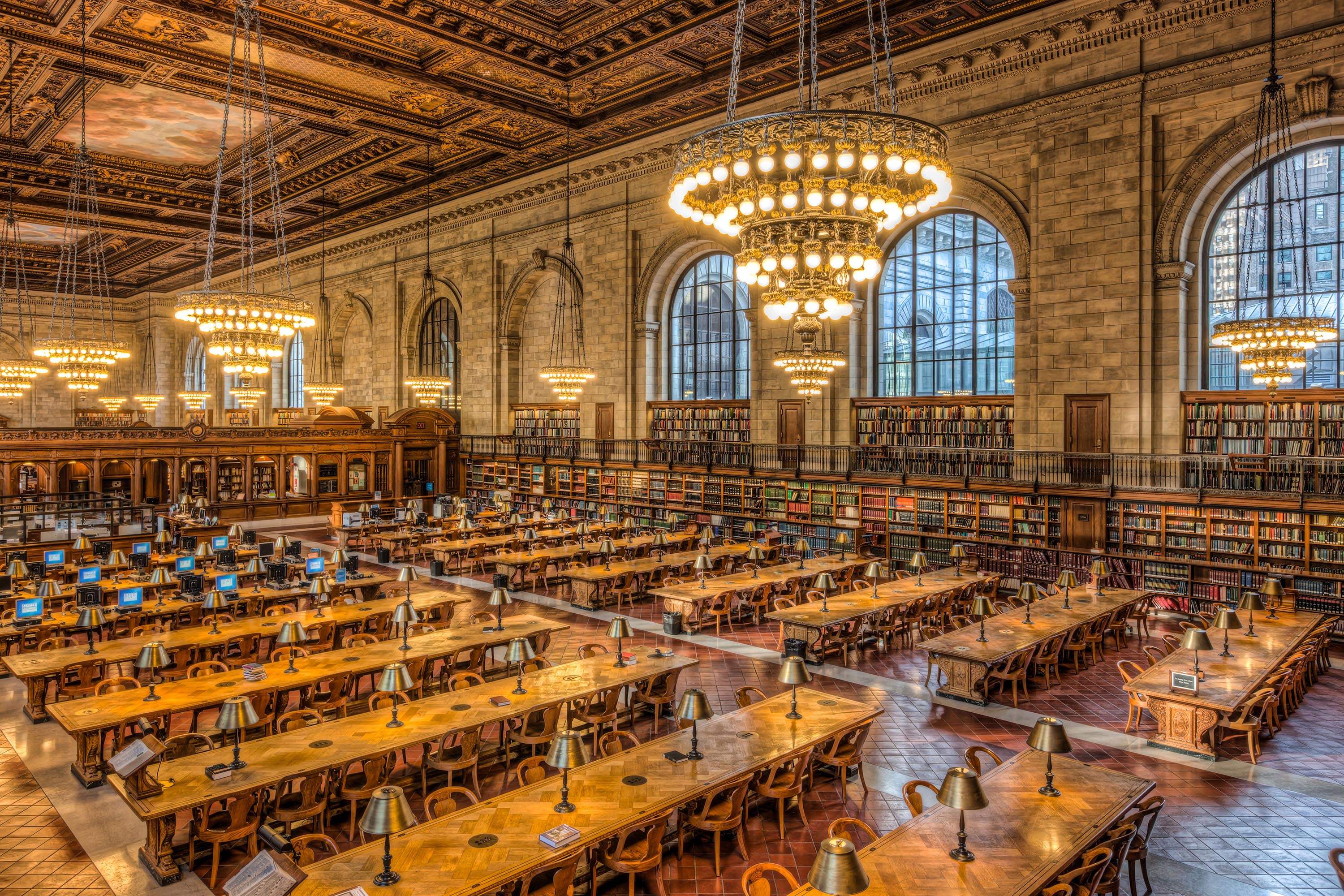

But the New York Public Library Main Branch, a Beaux-Arts marble palace of books, is one of the most impressive sights on Fifth Avenue. Opened in 1911, it boasts a majestic marble stairway, grand historic fountains, allegorical sculptures, guardian lions and (of course) six Corinthian columns.

Rose Main Reading Room, New York Public Library. Photo by Clarence Holmes. Photography, courtesy Alamy

The colossal building holds 2.5 million books, shelved among and beneath commanding murals, celestial frescoes and a barrel-vaulted rotunda. The setting makes the books appear votive, almost transcendent, as if writing were a gift to the gods.

Although not, perhaps, international thriller writing.

It turns out that my friend and I were engaging in library tourism, although I hadn’t known that was a thing either.

The virtual hub of international library tourism is the website Library Planet, a ‘crowdsourced travel guide for libraries’, which features posts with wonderful titles such as ‘The dok Library Concept Center of Delft, The Netherlands — makes me want to hang out all day’; ‘Ulyianovsk Regional Scientific Library, Russia — a library with a ballroom’; ‘Roving robots, kitchens and creativity at Tampines Regional Library’; and, my favourite, ‘Library of Songdo — No shoes in this pastel party of a library’.

Library Planet was founded by a Danish couple, Christian Lauersen and Marie Engberg Eiriksson, but recently they handed over the editorship to frequent contributor Stuart Kells, a La Trobe University academic and author of the highly regarded The Library: A Catalogue of Wonders.

‘If you’re travelling as a library tourist, it’s about libraries as spectacle,’ says Kells. ‘It’s about the amazing architecture, the striking interiors, beautiful books in the right context — bindings that match the shelves that match the timberwork that match the ceilings.’

In 2017, Kells took off on a world tour of libraries with his wife Fiona and their two daughters, Charlotte, then aged one (‘a lot of the time, we were carrying her around,’ he says) and Thea, then aged five.

They visited libraries in Asia, Europe and the United States, and packed up again a year later to look at libraries in Tokyo. In 2019, they toured libraries in Western Australia, including Perth and the Kimberley.

Some of the libraries, such as the medieval Abbey Library of St Gall in St Gallen, Switzerland, are long-established mainstream tourist attractions. At St Gall, says Kells, ‘People queue to get in — and not many of them are there to do research or to borrow books.’

The Kells family prized St Gall in part for its appeal as a ‘cabinet of curiosities’, which sets out to explore the richness of the world — and the breadth of human knowledge — through its exotic and eclectic collections.

‘St Gall has mummies in the main vaulted library and has incredible celestial globes and other artefacts from around the world,’ says Kells. ‘Those sorts of libraries are a bit like art galleries or scientific collections and museums.’

Kells particularly loved the British Library in London, the Houghton Library at Harvard University and the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC. Little Thea, now 10, has affectionate memories of the New York Public Library, with its collection of toys that inspired AA Milne to write Winnie the Pooh, and the children’s floor at the National Diet Library in Tokyo, and the dress-up room at the Folger.

Kells says he learned from his travels that ‘libraries are human places — they’re places where people leave traces of themselves behind — and that libraries reflect human personalities, human interests, and that they serve a human and humane function.’

‘And I think that’s congruent with the fact that we travelled with children,’ he says, ‘and we used them as places to eat and things like that. You can’t divorce the informational and conservational functions from people.’

Kells nominates Jane Cowell, CEO of Yarra Plenty Regional Library in Victoria, as ‘one of my fellow travellers in the library world — in a non-literal travelling space.’

Cowell confesses to being a library tourist for both business and pleasure. ‘The first thing I do when I go anywhere is find out where the library is,’ says Cowell. ‘I’ve done four library tours, because I’m a librarian and I go overseas only to visit libraries.’

Kells says that more than half the contributors to Library Planet work in the industry. I ask Cowell if she has met any library tourists who aren’t librarians. ‘It’s usually a well-meaning partner of a librarian,’ she says. Architects are also attracted to libraries — they love civic buildings — along with photographers, historians and, of course, international thriller writers.

Cowell says the pandemic has shown that people need to be with other people. They get lonely at home and libraries can provide quiet, relaxed spaces with few social pressures and without the ‘noise’ of advertising. ‘And where else can you go that also has really clean public toilets other than a public library?’ she asks.

Cowell loves Toronto Reference Library in Canada: ‘It has an amazing makerspace, where people can write and publish their own book,’ she says. ‘It has a book-publishing machine!’

She also recommends Aarhus Public Library in Denmark and Stockholm Public Library in Sweden. But perhaps the greatest of all Nordic libraries is the Helsinki Central Library Oodi, in Finland, an astonishing facility that includes the world’s only library sauna.

Vertical garden at the entrance to Woollahra Library, Double Bay, which opened in 2017. Photo by John Gollings.

Perhaps the largest number of library tourists in one place in Australia can be found among the staff of the Australian Library and Information Association (ALIA) in Canberra. ‘I am a serial library visitor,’ confesses Trish Hepworth, director of policy and education at ALIA. ‘I must have visited about 60 libraries overseas. I often think there are two ways to really immerse yourself in a culture. One is to go down to either the local supermarket or the local market and see what people are buying every day. And the other is to go into a library space and see what people’s cultural touchstone is.’

‘I like going to different types of libraries,’ says Hepworth. ‘There’s a lot to be said for dropping into local public libraries. When you’re travelling, their offer of free wi-fi and somewhere to charge your phone is very useful, but it’s also great just to see what information collections people care about. What does the local literature look like? What does the local publishing look like? What are their local programs? It’s interesting to have a look at the relative size of non-fiction collections compared to fiction collections or children’s collections. Specialist libraries can be fascinating, too. A lot of university libraries have amazing architecture and often exhibitions highlighting some of their special collections — and it’s those slightly more niche collections that really give you an insight into cultures.’

But Stuart Kells cautions against viewing libraries only as physical buildings. He says that he loves the State Library of NSW (and its Shakespeare Room in particular) but he disagrees with people who claim that it was the first library in Australia. The Shakespeare Room at the State Library of NSW. Photo by Joy Lai

‘That’s not true,’ says Kells. ‘There was a library here before Europeans got here. The library was held differently — it was in people’s heads, and it was conveyed orally, and there were physical records of it through artwork and other things. But there was a library, in the sense that there was a collection of texts and stories and science. The State Library of NSW might be the first European-style library, or it might be the first multistorey building that is a library, but it’s not Australia’s first library.’

Some of library tourists’s favourites

Aarhus Public Library, Denmark

The Aarhus Library in the university city of Aarhus is built on 30,000 square metres of land that was once part of a working port. It is vast and spectacular, with a gorgeous outside deck and harbour views.

‘It has a beautiful deep gong that goes from ceiling to floor, which chimes whenever a baby is born in Aarhus — and everybody stops and claps,’ says Jane Cowell. ‘It also has a carpark that is managed by a robot. You plonk your car in, and the robot takes it and stacks it.’

Bargoona Nganjin (North Fitzroy Library), Melbourne

Ground-breaking Bargoona Nganjin (the name means ‘Gather Everybody’ in the language of the Wurundjeri people) opened in 2017.

‘The central, circular part of the building is meant to represent the spine of a book, and the brick walls are like the covers opening out from the road,’ says Jacqui Lucas, learning services coordinator at ALIA. ‘It has a rooftop section with a kitchen that brings their multicultural community together weekly. It has the kitchen garden on the rooftop linked to their play area. People experiencing homelessness are very much welcome and the staff are caring and supportive. Also, there’s great youth spaces and the best disability-friendly toilet in Australia!’

Bargoonga Nganjin (North Fitzroy Library), Melbourne. Photo by Michael Gazzola

Folger Shakespeare Library, New York, USA

Founded by Henry Clay Folger, the onetime chairman of Standard Oil, the Folger has ‘by far the best Shakespeare collection in the world,’ says Stuart Kells. ‘The share of First Folios is just nuts. There’s 235 in the world. If you’re a major library like the British Library, and you have a lot of First Folios, you might have five. The Folger has 82!’

Gladstone’s Library, Hawarden, North Wales

Gladstone’s Library was donated to the nation by former British prime minister William Gladstone. ‘It’s an absolutely drop-dead gorgeous Gothic-revival building, very photogenic,’ says Phoebe Weston-Evans, program officer and researcher at ALIA. ‘The public can peek in, and anybody can get a reader’s card. I drove with my mum in a hire car to North Wales to see it.’ Gladstone’s styles itself as ‘the UK’s only residential library,’ with 26 hotel rooms for visitors. ‘The rooms have a wallpaper with books,’ says Weston-Evans. ‘They’re a bit kitsch. We decided to stay at an Airbnb instead.’

Gladstone’s Library, Hawarden, North Wales. Courtesy Library Planet

Library of Congress, Washington DC, USA

‘The Library of Congress is amazing, incredible,’ says Stuart Kells. ‘It’s the Americans trying to outdo Europe — and trying to outdo Rome, I guess. It’s all marble and these incredible rooms of columns, and then the central dome, which is just vast, and it has a very strong ethos of access.’

‘We went there with a one-year-old and a five-year-old, and the librarians were over the moon,’ says Stuart Kells. ‘They said, “Please come in! Here’s the area where there’s the puppet show! Here’s the area where they can do craft!”’

Library of Congress, Washington DC, USA. Photo by Alan Novelli, Courtesy Alamy

National Library of New Zealand, Wellington, NZ

The National Library of New Zealand must be one of the friendliest libraries in the world, although you’d never guess that from the outside. ‘It’s a brutalist building, which is not necessarily my cup of tea, but it’s really striking,’ says Barbara Lemon, executive officer of National and State Libraries Australasia. ‘There’s a long-term exhibition, “He Tohu”, which includes a display of the original Treaty of Waitangi, as well as the original suffrage petition (New Zealand being the first country to award the vote to women) and the Declaration of Independence of the United Tribes of New Zealand. The exhibition that has been buIlt around those in a wooden cave-like space, which has a huge significance to Maori. When I visited recently, the experience was deepened by joining a little primary-school tour from near Dunedin — a group of sheep-farming-family kids — who came to have a look inside this dark cave and fully participated. In the end, they were offered the chance to do a waiata (a poem or farewell song) to recognise the space, and they did a haka on the spot. Which was pretty amazing in the dark. And the Home Café does a good cheese scone.’

National Library of New Zealand, Wellington, NZ. Photo by Paul McCredie

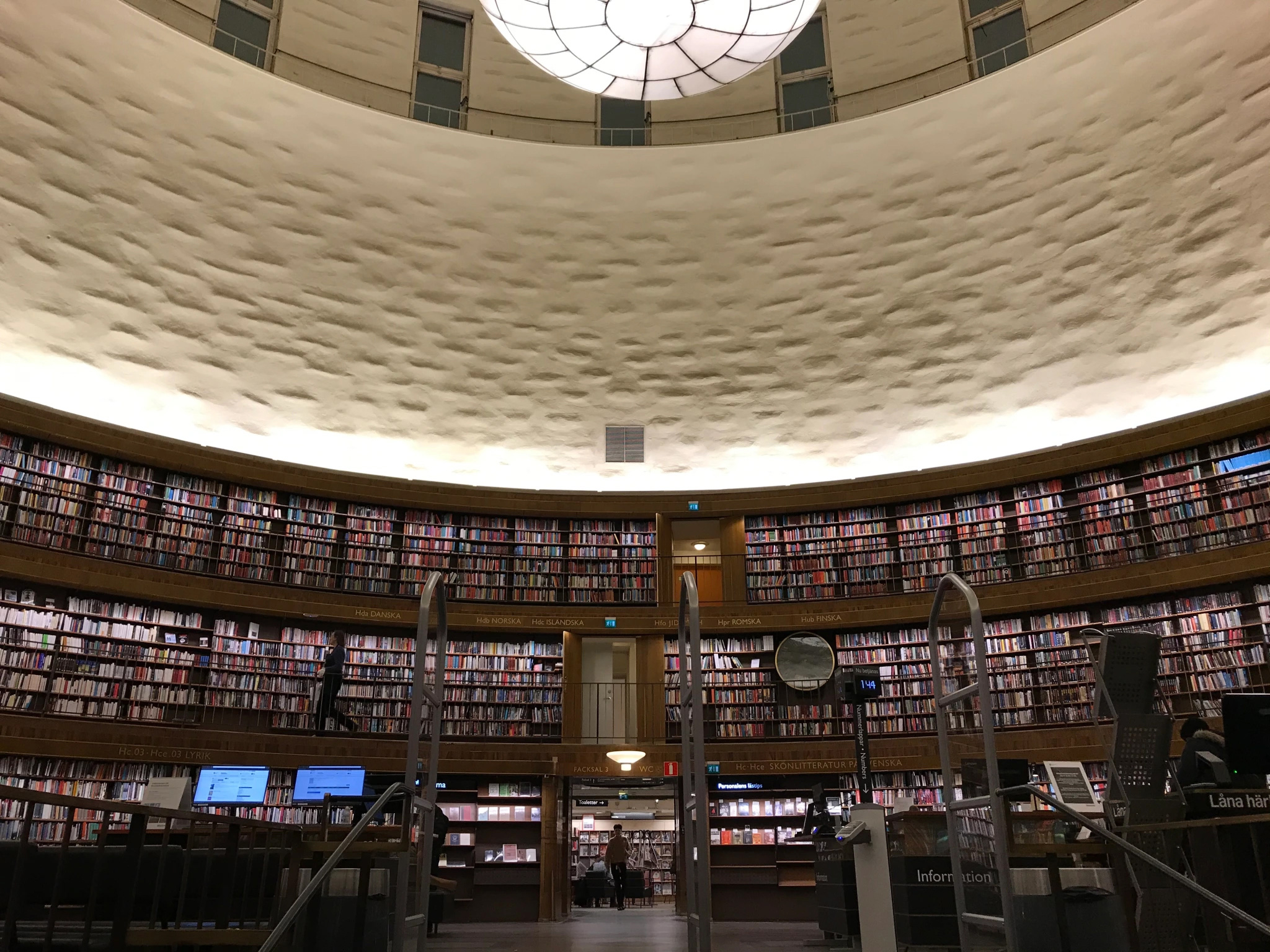

Stockholm Public Library, Sweden

Stockholm Public Library opened in 1928 in a distinctive round building.

‘You go in through dark marble,’ says Jane Cowell, ‘because the architect envisaged that you would walk into a circle of three storeys of stacks of books around the walls and go from the darkness and into the light.’

‘Obviously, it isn’t modern. You have to walk upstairs — there is no disability access; you wouldn’t want it now — but it is an absolutely beautiful library, and we were serenaded by a virtuoso violinist who’s also the librarian.’

Stockholm Public Library, Sweden. Courtesy Library Planet

Mark Dapin is a novelist, historian, true crime writer, journalist and screenwriter.

This story appears in Openbook autumn 2023.

On literary merit

We may find it easy to give a book one star, or five, but what do we really mean by the phrase ‘literary merit’?

And the winner is …

What impact do prizes have on Australia’s literary ecosystem?

Surface art

Book cover design is an intricate and sometimes baffling process that brings together authors, readers, publishers, booksellers and designers.