Construction of Sydney City Railway, 1922-1923 / photographed by J. Bradfield

a1624058

By Vanessa Berry

Vanessa Berry at the Commercial Travellers’ Association club, Sydney, photo by Joy Lai

Last year, a man out riding his bicycle in Sydney’s northern suburbs noticed a photograph album in a pile of hard rubbish awaiting council pickup. After rescuing it, he contacted the Library. This lucky roadside find on a suburban street has added an interesting album of photographs to the Library’s collection.

The album commemorates the opening of the Domain Express Footway, a moving walkway connecting the Domain Parking Station with the city. This may seem like a humble achievement, but when it opened in 1961 the footway was of international significance: it was the first to be built in Australia, and the longest in the world.

The dark blue covers of the large, square photograph album are embossed with the words: ‘Compliments of Morison and Bearby’. This was the engineering company from Newcastle that compiled the album and presented it to Sydney’s Lord Mayor. Holding it now, I think of all the hands the album has passed through: its compiler’s, the Lord Mayor’s, the hands that discarded it and those that saved it.

As I open the album I’m transported to 1960, when construction work was beginning on the footway. It was a transitional era in the city’s history, and one of rapid change. Since the 151-foot building height restriction was lifted in 1957, Sydney had begun to grow tall. On the ground the extensive tram network had been almost entirely dismantled, as city planners anticipated the increasing popularity of the motor car. The footway was to be part of this new, efficient Sydney, built for the future.

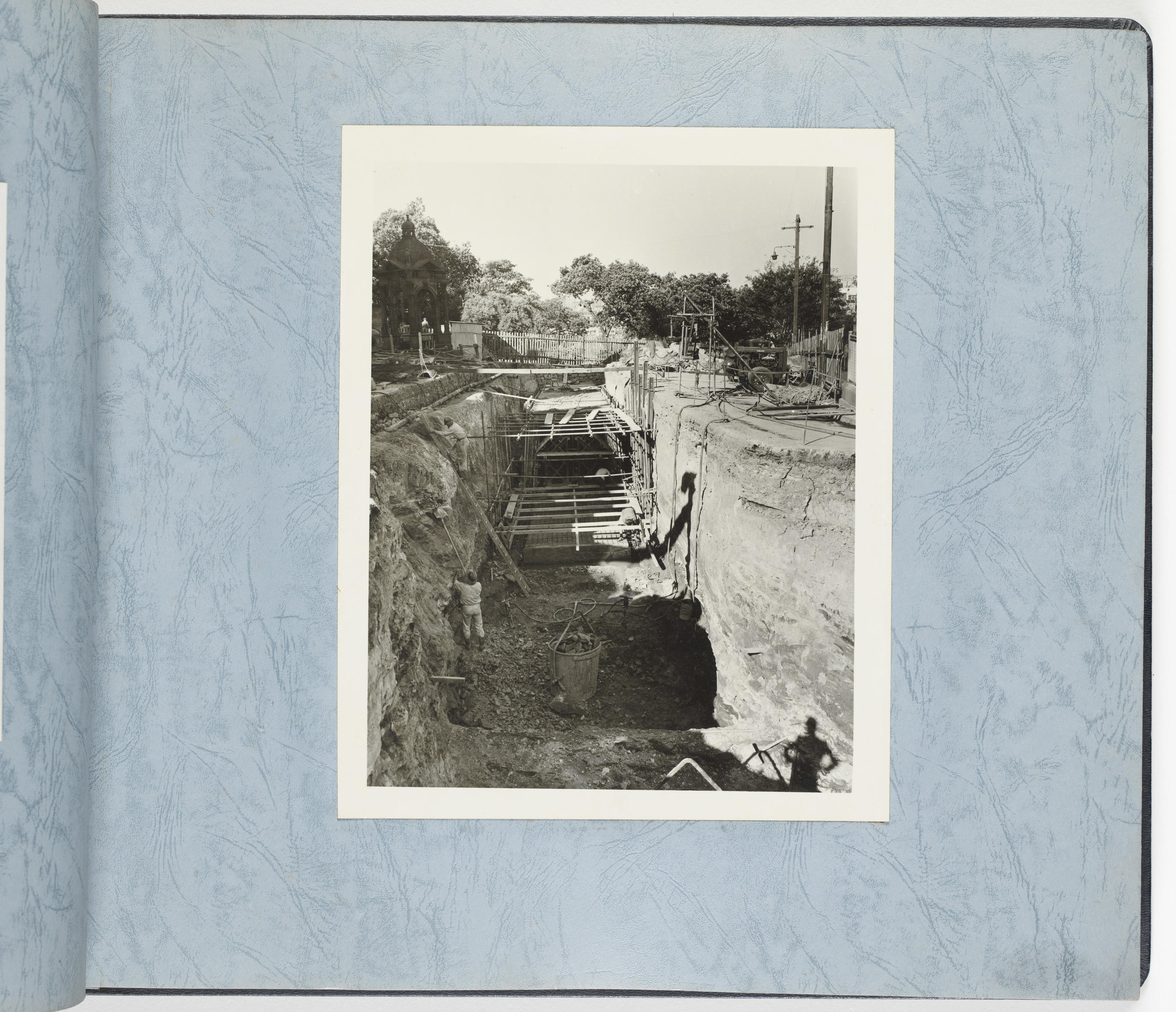

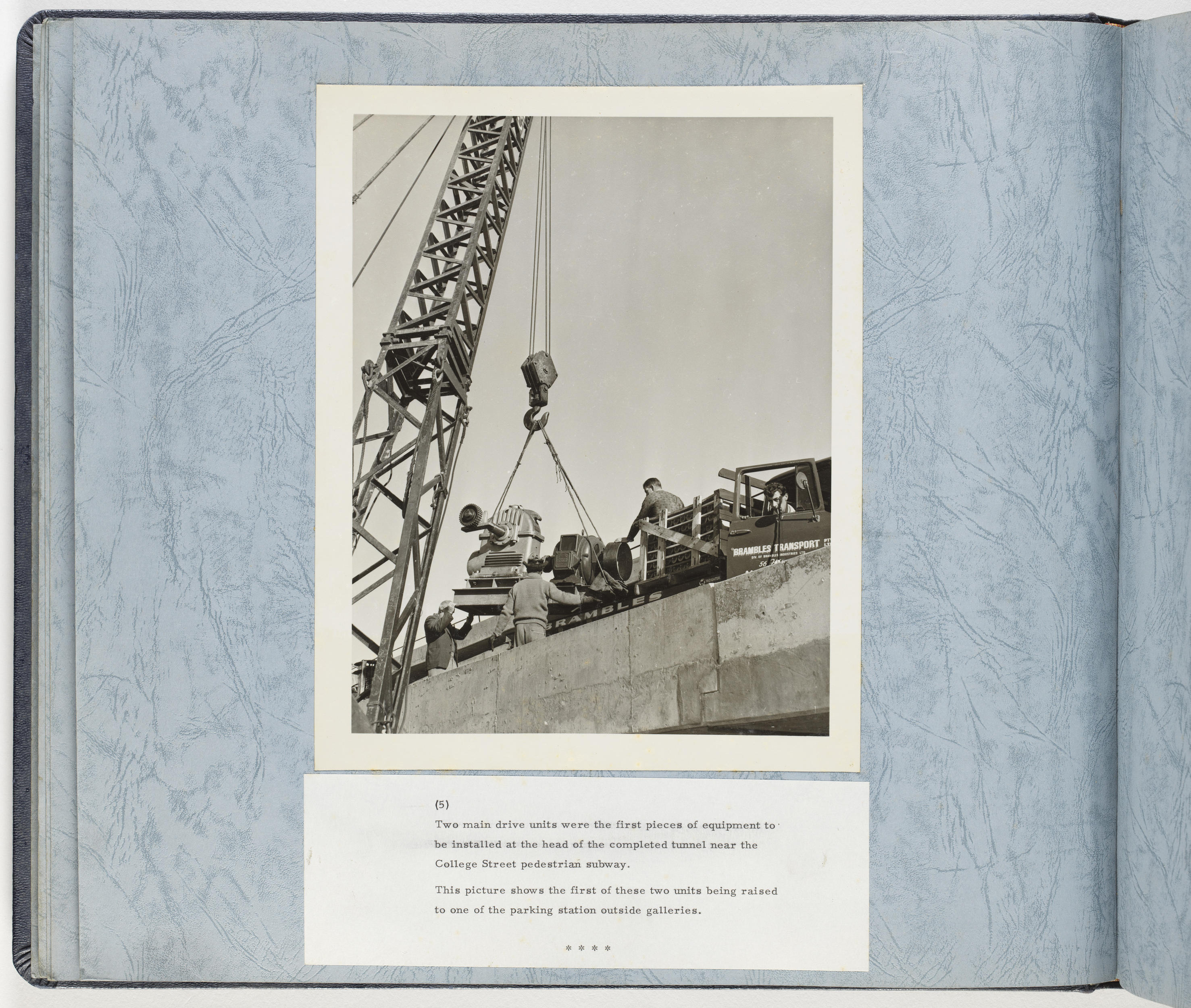

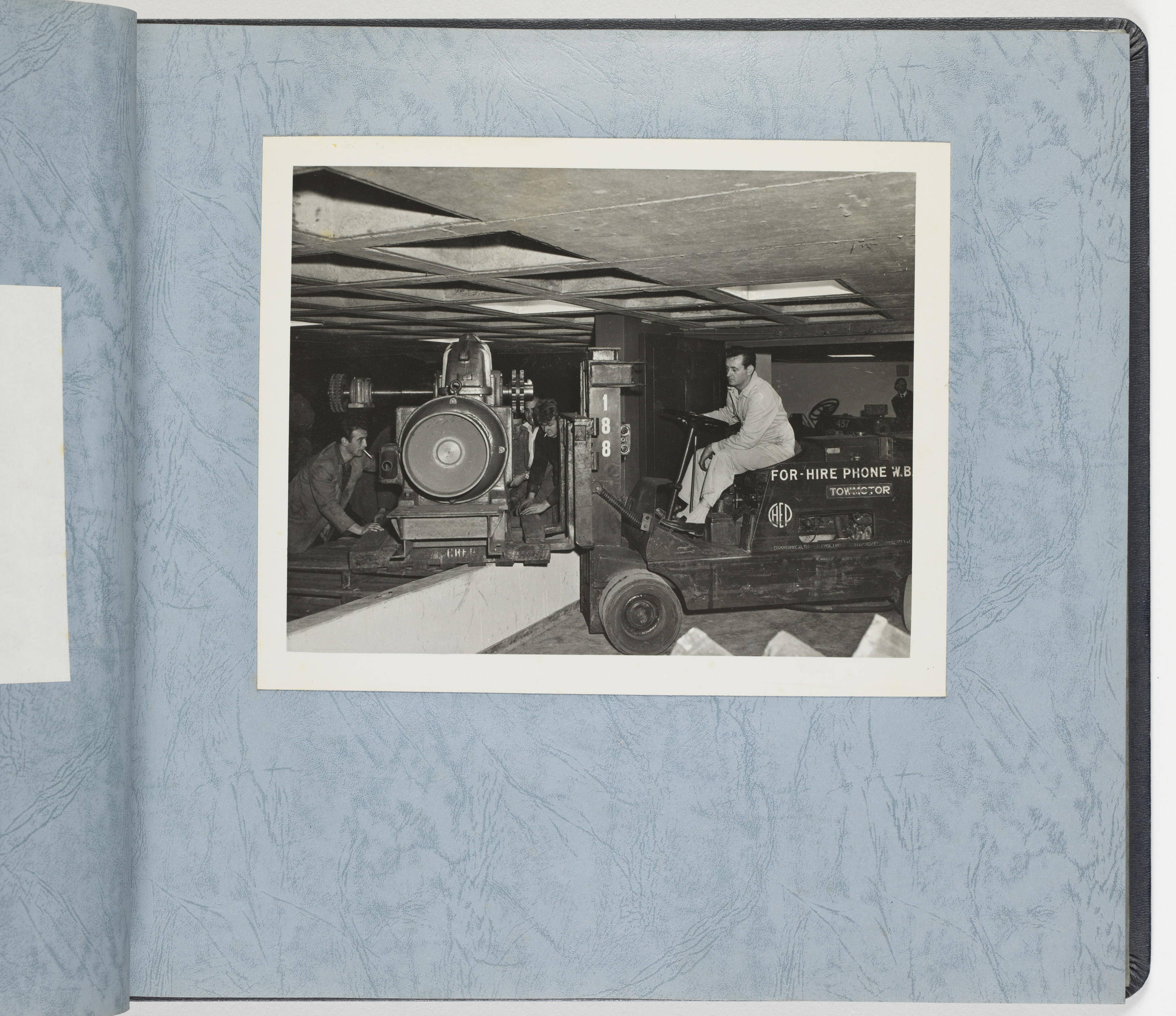

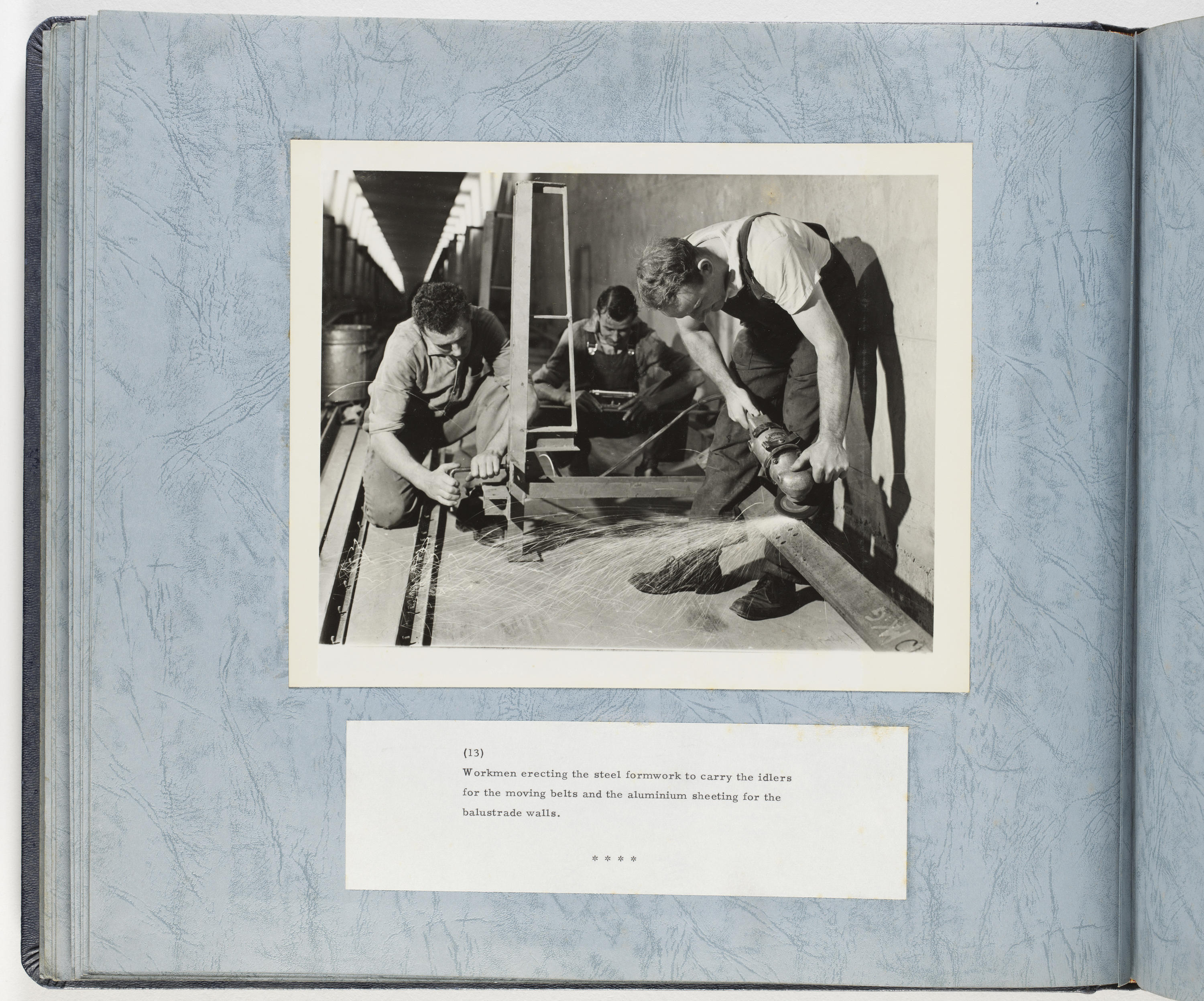

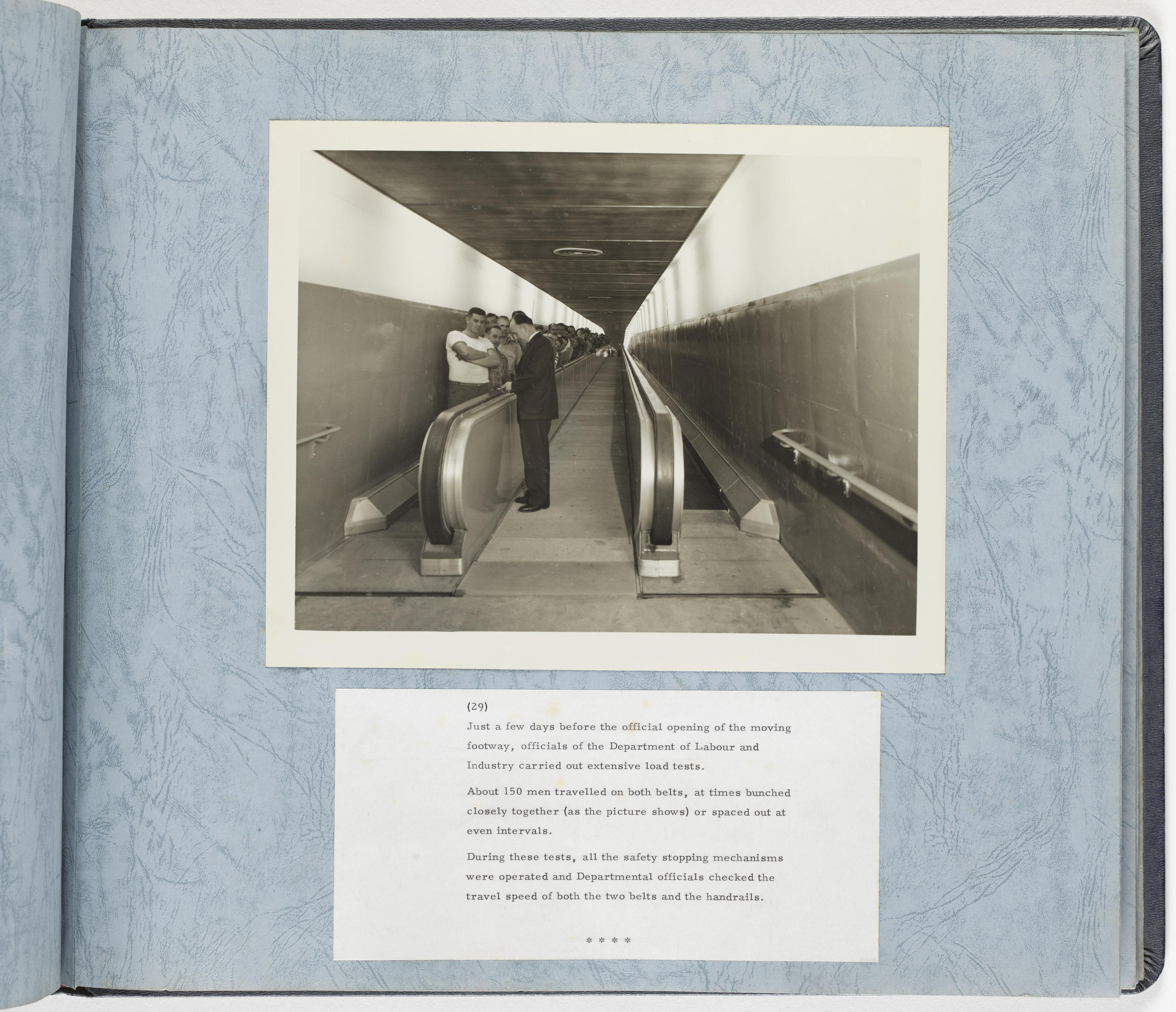

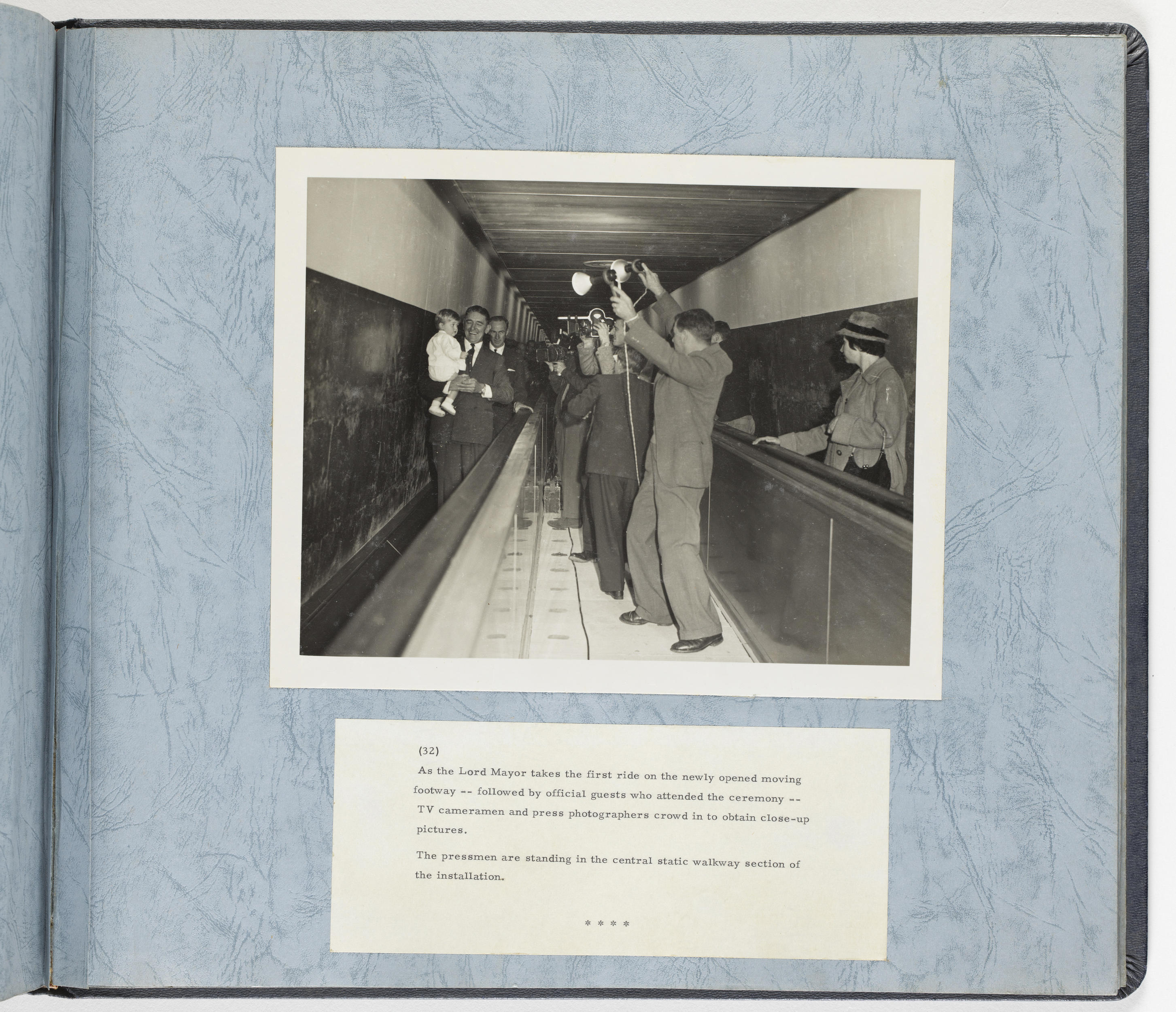

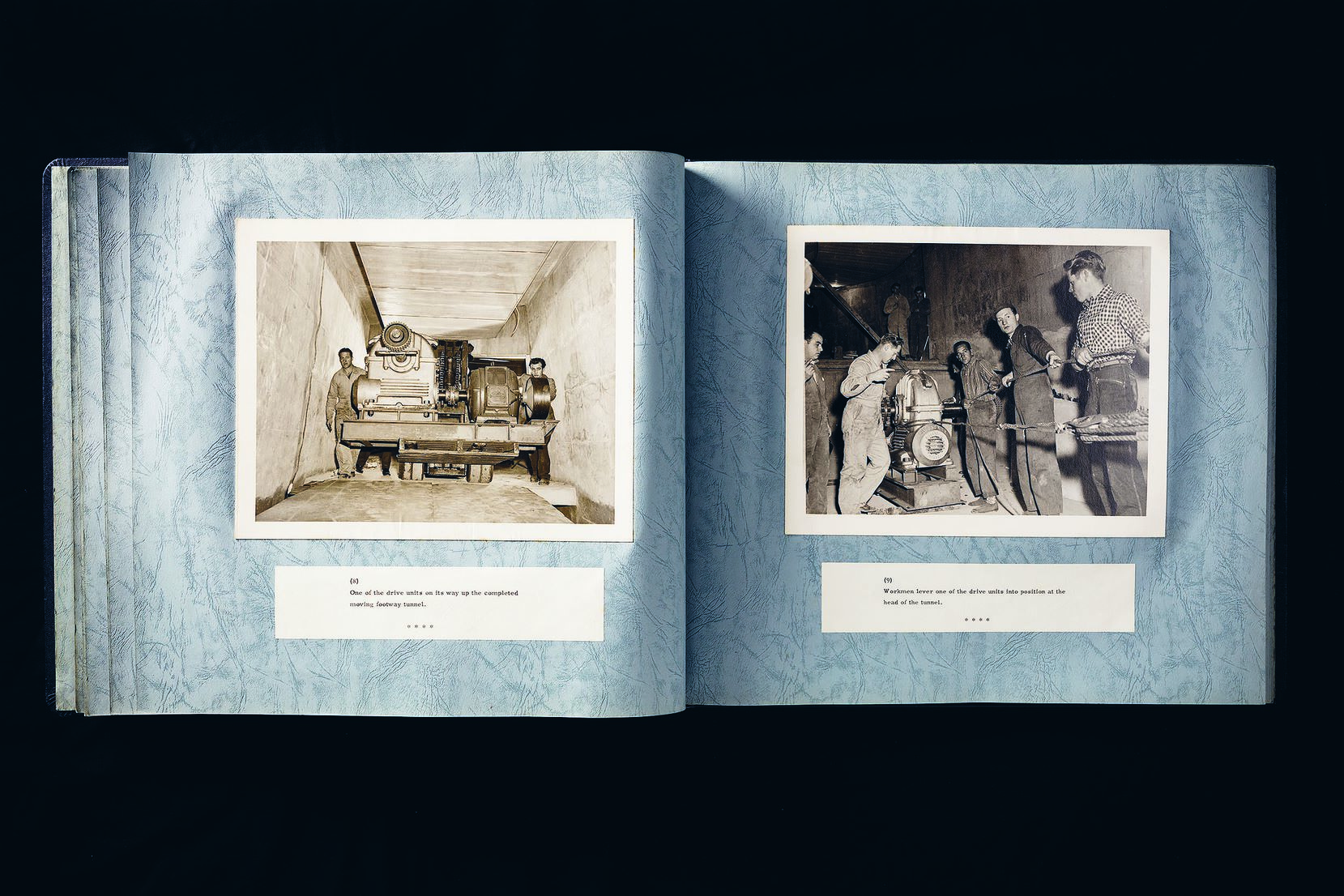

The story begins in a trench cut down the centre of the road, where men wearing overalls and caps labour. Then large, heavy pieces of machinery are put in place by cranes and forklifts. In the middle of the album there are images of the empty, still tunnels. Work has ceased and the footway construction is complete. The rest of the album is populated by officials: men in suits, the press with cameras and microphones, and the smiling Lord Mayor Harry Jensen and his 13-month-old son taking the first ride on 9 June 1961.

The people riding the footway that day would have felt as though they were experiencing the future, but I’m drawn to details that locate it in the past. Labourers wearing collared shirts and overalls have cigarettes in their mouths as they perform ‘a particularly tricky manoeuvre’, guiding one of the drive units into the tunnel.

Other scenes stand out for their serendipity. Among the 150 men lined up along the footway to test its load-bearing capacity, I notice one at the front of the line, with his broad arms crossed, whose white T-shirt and dark trousers neatly match the two-tone paintwork of the tunnel.

The footway must have seemed like the fulfilment of predictions. For decades, moving walkways had been promoted as a new way to manage growing city crowds. A 1928 Sun article described the ‘flattened escalators’ that would replace footpaths, alongside other anticipated transport innovations. ‘Most buildings,’ the article declared, will have ‘landing grounds for aeroplanes’.

Illustrations from the 1920s show a future city with aerial transport weaving above and between skyscrapers. In ‘Design for a Future Martin Place’, drawn in 1928 to illustrate ideas by engineer and architect Norman Weekes, aeroplanes roost in high-rise hangars. The sky is full of tiny planes, their density mirroring the groups of human figures in the square below.

Such images might seem fanciful today, but they capture the sense of possibility inspired by advances in technology. Then, as now, people imagined the future city with optimism.

In the 1970s the Wynyard Pedestrian Network plan presented a more pragmatic vision: a streamlined city-wide pedestrian movement system. The scheme came with a hefty list of interconnected elements: ‘widened footpaths, boulevards, colonnades, arcades, subways, bridges, railway station concourses, malls, plazas or terraces and parks’. Disused tram tunnels would be converted into a moving walkway connecting Wynyard station with the high-rise office district that was planned for The Rocks. But The Rocks redevelopment never came to be, and no moving footway was installed. The tram tunnels now form part of an underground parking station.

Sydney can be thought of as two cities: the aboveground, with its office buildings, streets and parks, and the underground, a city of tunnels and pipelines, basements and parking lots. The two cities have grown in tandem.

Decades before the Domain Moving Footway was constructed, another, much larger, underground construction project heralded the Sydney of the future: the new City Circle railway line, designed by chief engineer John Bradfield.

Like the footway, this construction is meticulously recorded in a series of photographs. In two thick, leather-bound volumes, we see the viaduct built to the north of Central Station, and Hyde Park becoming a series of wide, deep pits. The small figures of men, horses and lorries working inside the trenches show the scale of the operations. Crowds peer through the hoardings, watching the railway take shape. As we flip through the albums, we join these onlookers in watching the railway’s day-to-day progress.

The city in the background is both familiar and distant. Some buildings are recognisable, like the turrets of Mark Foy’s department store on Elizabeth Street, now the Downing Centre courthouse. Other details belong to a city long past: triple-storey commercial buildings with awnings and iron lace, walls covered in painted advertisements for tea and tobacco companies, cars with spoked wheels and canvas canopies.

As the album continues, the construction of the tunnels slowly progresses until a concrete shell encases them. Hyde Park is reinstated, ahead of the opening of the line in 1926. By the time the Sun was predicting the ‘beach skyscrapers’ and ‘wireless telephony’ of the future city, trains had been moving through the newly built tunnels for two years.

As remote as these images of Sydney can seem in sketches, plans and photographs, they are connected to everyday experiences in the present-day city. Although a network of moving walkways was never built, the Domain Express Footway still conveys people to and fro. Hundreds of trains carrying thousands of passengers travel through the City Circle tunnels daily, while up above a new cycle of rapid change works to reshape the city.

Vanessa Berry is a Sydney writer and artist, whose latest book is Mirror Sydney (Giramondo, 2017). The Library has acquired the original artwork for her book.