Remembering Australia’s women writers

Remembering Australia’s women writers

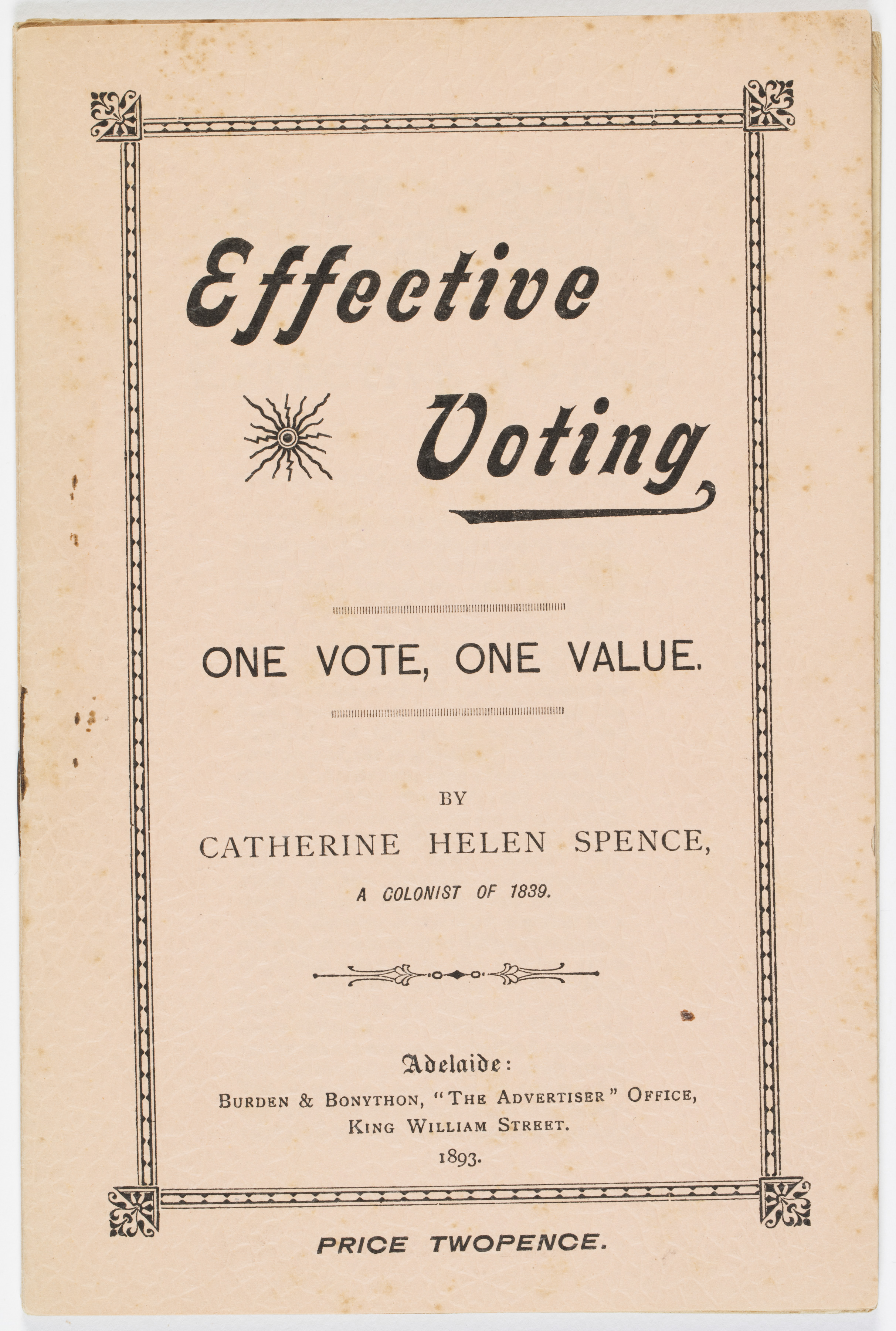

Spence worked tirelessly throughout her life for children’s welfare and educational reform in South Australia. She is now largely remembered for her advocacy of women’s rights and electoral reform, as well as her novel of the ‘gold fever’ in South Australia, Clara Morrison (1854). Her role as children’s author and educationist, however, was both formative and influential in South Australia.

Spence founded the first children’s library in Australia in Adelaide in 1859 and contributed regular children’s columns to The South Australian Register and The Adelaide Observer. At the request of the South Australian education board, she also wrote an economics primer for schools, The Laws We Live Under (1881). In this text, Spence makes explicit the relationship between education and the nation. The ‘well-being of the colony’, she writes, ‘depends very much on all its children being prepared for the duties of citizenship by receiving a good plain education.’

Spence’s short stories for children, which were serialised in State newspapers and school readers, follow in the didactic vein of Edgeworth’s moral tales. [v] Critics have largely ignored the significance of these stories and dismissed them as aesthetically uninteresting, but they arguably demonstrate Spence’s broader educational beliefs and her active response to leading discourses and debates in Australia on children’s education.

Like Edgeworth, Spence’s educational philosophies promoted rational thinking opposed to rote learning. ‘Education’, wrote Spence, ‘has a twofold aspect … it is meant to teach many things necessary to be known, and it is meant in a still higher degree to train the mind.’ Her stories for children regularly feature young protagonists who are forced to use their developing critical faculties to make rational and moral judgements on their own. Those judgements are also seen to have a wider bearing on the more general socialisation of the child as a future citizen of the nation.

In addition, many of Spence’s retellings of traditional fables and legends – including ‘The Three Little Pigs’ and Irish folk tale ‘The Legend of Bottle-Hill’ – foreground female protagonists as intelligent and rational characters. Spence makes her advocacy of equality between the sexes in both school and the nation clear in The Laws We Live Under. ‘There can be no greater mistake for girls to make’, writes Spence, ‘than to suppose they have nothing to do with good citizenship and good government.’

Professor Susan K. Martin (La Trobe University), Assoc. Professor Tanya Dalziell (University of Western Australia) and Dr. Anne Jamison (Western Sydney University).

The too easy dismissal of Spence’s writing for children is thus both questionable and a reflection of the broader neglect of critical study on Australia’s nineteenth-century women writers. On 3 November, 2016, award-winning female writers and leading scholars from across Australia convened for a symposium at the State Library to redress this issue and share their thinking on the ongoing significance of nineteenth-century Australian women’s writing. [vi]

Emily Maguire, Schools Ambassador NSW for the Stella Prize

The symposium included a presentation on Spence and education, as well as a talk by author and NSW Ambassador for the Stella Prize School Program, Emily Maguire. Emily spoke on the current gender inequities in Australian school curricula and recommended reading for children. Contemporary Australian women writers, Maggie Mackellar and Jessica White, also discussed with Sydney Review of Books editor, Catriona Menzies-Pike, their retrospective reviews of nineteenth-century authors, Spence and Rosa Praed (1851-1935). [vii]

Australian author, Maggie Mackellar.

Concerns around the ways in which we value and understand contemporary women’s writing in Australia repeatedly overlapped in these discussions with how Australia’s historical women writers have been positioned within Australia’s literary history. [viii] The interconnections between past and present constantly reminded how necessary study and appreciation of historical women’s writing still is in Australia. Especially in terms of rethinking and challenging dominant cultural attitudes towards contemporary women’s writing. As Maggie Mackellar encourages in her essay on Spence, ‘read her to see where we have come from and read her to see how far we’ve still got to go.’

Ethel Turner's Seven Little Australians

"We have decided to go to Lindfield. It will be like being buried alive to live in a quiet little country place after the bustle and excitement of town life."